As the United States marks its 250th anniversary, WTOP presents “250 Years of America,” a multipart series examining the innovations, breakthroughs and pivotal moments that have shaped the nation since 1776.

Knox Systems is proud to partner with WTOP to bring you this series.

Modern cloud micro‑segmentation is rooted in a straightforward but powerful concept: If an attacker breaches one part of a system, the rest should remain secure.

By dividing networks into small, isolated segments and tightly controlling access between them, organizations greatly reduce the chance that a single intrusion will spread.

The idea underpins today’s conversations about “granular security zones,” “containment boundaries,” and the prevention of “lateral threat movement.” Although these terms are born of the digital age, the underlying strategy has a surprisingly deep historical parallel.

Long before cloud computing, a similar approach proved invaluable in a very different battleground — the intelligence operations of the American Revolution.

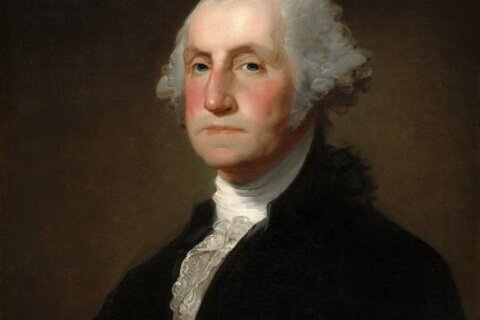

During the Revolutionary War, Gen. George Washington built a covert intelligence network that embodied micro‑segmentation.

Drawing on lessons from earlier military service, including the French and Indian War, Washington understood that his underpowered Continental Army could not defeat the British through brute force alone, according to George Washington’s Mount Vernon. Superior intelligence — gathered quietly, shared carefully, and protected at all costs — would be essential for countering one of the premier military powers of the 18th century.

In 1778, he oversaw the creation of a spy network operating inside and around British‑occupied New York City, according to reports in the National Archives and elsewhere. Historians say the individuals involved were not professional operatives, and that most were ordinary farmers, merchants and townspeople. Yet they became part of a remarkably disciplined “need‑to‑know” system in which no single person held the full picture.

Documents in the Library of Congress show that agents were assigned code numbers instead of names, and even Washington was referred to only by his own numerical identifier. The anonymity was intentional: If a member was captured, there was little information they could reveal simply because they did not possess it. The network functioned like isolated security segments — each aware only of what was necessary to accomplish a specific task.

Historians at Mount Vernon say the techniques these citizen‑spies used were inventive and varied. They wrote messages using invisible ink, created coded references for people and places and even used subtle signals — such as the positioning of clothing on a clothesline — to communicate from a distance.

They also relied on “dead drops,” hiding letters in fields, underbrush and buried containers, so intelligence could move without requiring dangerous face‑to‑face meetings.

Although self‑taught, many of the methods they adopted mirrored established European military spycraft, according to the Long Island History Journal.

Experts at Mount Vernon go on to say that life in the network was filled with danger. Couriers traveled alone on treacherous, hostile roads, operatives posed as loyalists to move undetected and every checkpoint carried the risk of exposure.

To protect themselves, messages were often destroyed or copied to leave no traceable originals. The group also depended heavily on trust built within a tightly knit community, whose members insisted on working only with people they knew personally.

Despite the risks, the intelligence gathered had real strategic impact. In one notable case highlighted by the caretakers of Washington’s estate, the spy network uncovered a British plan to ambush newly arriving French allies. Armed with this information, Washington shifted his forces and made the British abandon the attack. It was a vivid demonstration of how compartmentalization, secrecy, and disciplined information flow — hallmarks of micro‑segmentation — could produce decisive results.

More than two centuries later, public interest in this clandestine world surged as a result of the AMC drama “Turn: Washington’s Spies” (2014—2017), which highlighted just how innovative and effective these early intelligence methods truly were.

Get breaking news and daily headlines delivered to your email inbox by signing up here.

© 2026 WTOP. All Rights Reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.