CHARLOTTESVILLE, Va. — Just hours after Charlottesville leaders had the controversial statue of Robert E. Lee in Emancipation Park covered in black, an Ablemarle County man attempted to take down the tarp.

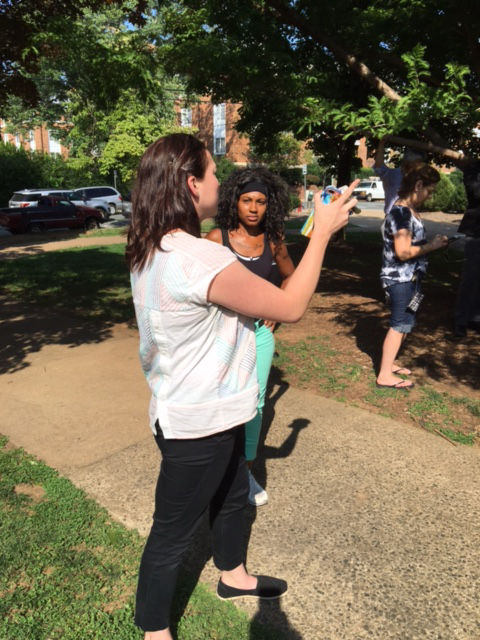

Shortly after 4 p.m. Wednesday, John Miska, a veteran and self-proclaimed free-speech advocate wearing a tie-dye T-shirt and carrying a legal weapon, cut away a small section of the black covering before Charlottesville police ordered him stop.

Miska complied with the order, but claimed the covering violates a state law banning the takedown of Confederate monuments. He was not arrested.

After Miska stopped and walked a few steps from the statue, he made an impassioned plea to about four dozen onlookers to uncover the statue and keep it in the park. He argued that removing it erases American history.

“This was an American,” said Miska referring to Lee. “He fought for the wrong ideas. He fought for the wrong ideals.

“But we need him to be here, so we can point to him and say he fought for the side that lost. He repented. By covering up this statue, we’re committing a great wrong to anyone who’s an American.”

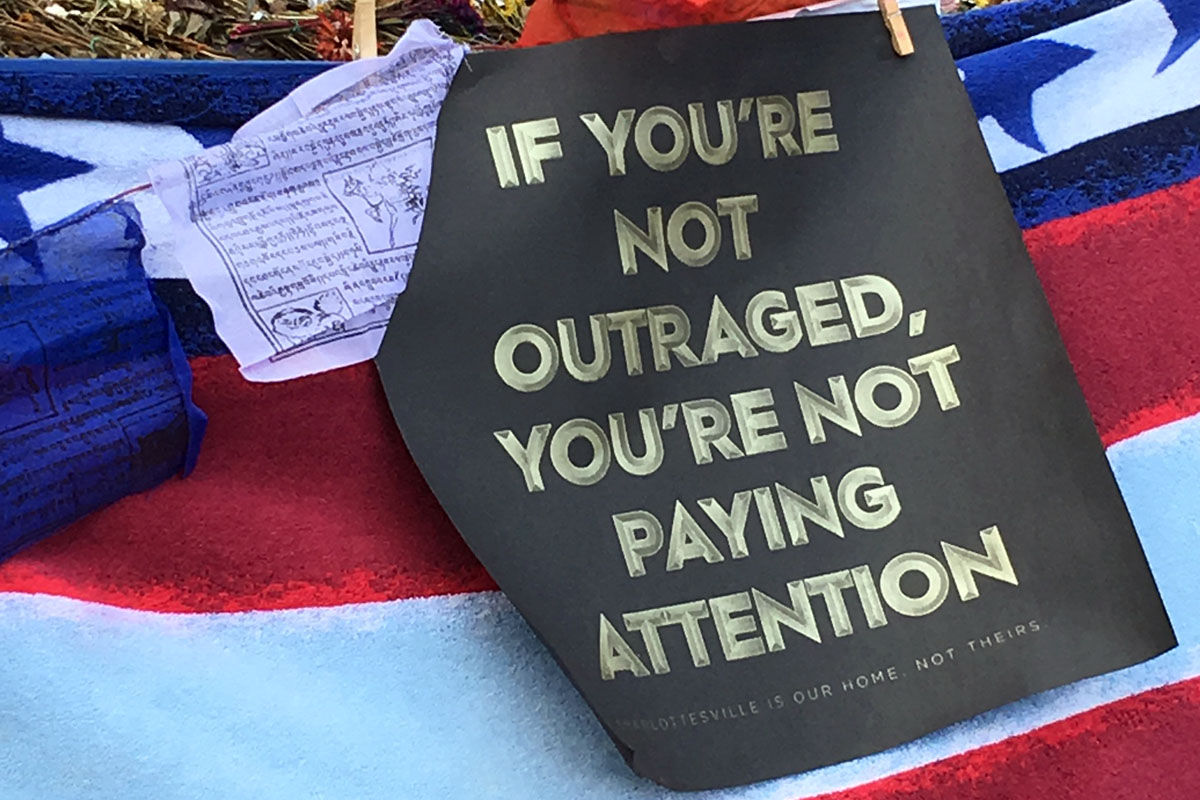

Monday evening, after a loud and contentious session involving hundreds of angry statue opponents, the Charlottesville City Council voted to cover the Lee statue, along with a statue of Confederate general Stonewall Jackson located in another city park.

City workers covered the Lee statue early Wednesday afternoon.

As Miska cut away at the covering, one onlooker called him “a coldhearted bastard.”

But later Miska argued, “If they can do this to this memorial, what’s to stop them (from saying) John Kerry was right, we need to go down and cover the Vietnam War memorial,” referring to Charlottesville’s monument to Vietnam vets in McIntire Park.

Former Secretary of State Kerry, a Vietnam Vet, became famous in 1971 for a speech before Congress where he denounced American involvement in that war as immoral and “barbaric.”

Miska also said he attended the Aug. 12 White Nationalist rally in Emancipation Park, and claimed he was physically confronted by both neo-Nazis and what he called “Communist” protesters for standing up for free-speech rights.

Several onlookers argued with Miska, saying the statues were divisive and needed to come down.

Miska countered by saying the main problem in Charlottesville wasn’t the statues themselves, but “failure of discourse” about the subject.

Miska, of Barboursville, Va., was one of several plaintiffs of a federal lawsuit against the government early in the decade, claiming their First Amendment rights were violated when they banned from passing out literature on the National Mall. They won the suit.