NEW YORK (AP) — For the last few years of its life, HBO’s “Real Sports” taped its episodes on the same Manhattan block where CBS’ “60 Minutes” resides. They shared a sensibility along with a neighborhood.

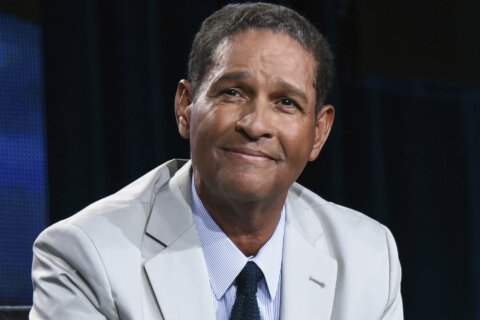

But while “60 Minutes” rolls along in its sixth decade, the monthly sports magazine helmed by Bryant Gumbel is calling it quits in its 29th year. The final, 90-minute episode premieres Tuesday at 10 p.m. Eastern.

Sports was a lens through which the magazine looked at all manner of issues, winning awards for pieces on corruption at the International Olympic Committee, labor abuses as Qatar prepared for the World Cup, concussions in sports and children forced to be jockeys for camel races in the Middle East.

“Real Sports” told some inspirational stories, like Mary Carillo’s profile of the Hoyts, a father who ran marathons pushing the wheelchair of his son with cerebral palsy son, and flashed humor.

Who won or lost? There were other guys for that.

“I’m OK,” Gumbel said before taping the last episode. “I’m sad, but everything has to end at some point and this is the right time for this to end.”

Backstage, a cart filled with champagne was wheeled down a hallway. Correspondents, producers and their families wandered through offices, saying farewells. Gumbel’s wife, Hilary, and his grandchildren settled into seats in the control room to watch the final taping.

A LONGTIME ENDEAVOR

Gumbel is 75, at the end of a contract, and HBO is now controlled by a company, Warner Bros. Discovery, on the hunt for cost savings. While the show’s exit makes sense, the fear is that a form of sports journalism is leaving for good, too.

“It has been the gold standard in sports journalism on TV for the last three decades and it really is quite a loss,” said Mark Hyman, director of the Shirley Povich Center for Sports Journalism at the University of Maryland. “It checked all the boxes — timely, ambitious, well-funded, independent.”

Increasingly, sports news comes from outlets owned by leagues, like the NFL or MLB networks, or networks whose businesses depend greatly on winning rights deals, he said.

“The show tried to do some things in sports journalism that no one else was doing,” Gumbel said. “I think it was one of the few avenues that could honestly explore issues without having to worry about ratings or sponsorships or relationships.

“I’ve been on the other side of that coin,” he said. “I’ve worked for networks who were what they would call now the ‘broadcast partner’ of a sports entity. And you’d only be a fool to think you can follow any story wherever it wants if it collides with that relationship. Life doesn’t work that way.”

When athletes agreed to appear on “Real Sports,” they knew they were agreeing to a challenging interview, much like “60 Minutes” guests knew what they were signing up for, Carillo said.

Now athletes can control their own messages through social media or outlets like The Players’ Tribune, she said.

“I wish we could have kept going,” she said. “But times have changed.”

THE STORIES — AND DISAGREEMENTS — THAT RIPPLED

Carillo has been with “Real Sports” since 1997. Other prominent correspondents have included Jon Frankel, Andrea Kremer, Armen Keteyian, Soledad O’Brien and David Scott. The late sportswriting legend Frank Deford was on from 1995 to 2014.

Bernard Goldberg was a prolific correspondent until a bitter exit in 2020. He said he got angry with something Gumbel said about the extent of racism in society and abruptly quit the show after 22 years.

Goldberg said he canceled HBO the day he quit, hasn’t seen a minute of “Real Sports” since and won’t watch the finale. He declined further comment.

Ask Gumbel about stories he did that have stuck with him, and he mentions one that resulted in the release of an athlete, Marcus Dixon, from prison and another about a recruiting scandal at St. Bonaventure University in which a university official committed suicide.

“We offer a focus on how athletes impact their sport,” he said. “What’s more important to me, more lasting to me and more interesting to me is how sports impacts the people who try to play it, try to run it and try to govern it.”

Gumbel takes pride in having never missed a show taping in 29 years despite a divorce, two bouts with cancer, seven surgeries and a particularly gruesome face injury — he showed a picture on his phone — that required 68 stitches.

He recalls conversations with Deford about age diminishing the ability of people in their line of work. “Frank used to tell me, ‘I can still turn a phrase. I just can’t do it as often as I used to,’” Gumbel said.

He can relate. Gumbel has considered what many athletes contend with at the end of their careers.

“I’ve always thought I’d rather leave a year too early than a day too late,” he said. “I never wanted to be the guy who overstayed his welcome.”

___

David Bauder covers media for The Associated Press. Follow him at http://twitter.com/dbauder

Copyright © 2024 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, written or redistributed.