WASHINGTON — In the midst of the opioid epidemic, an easy-to-use nasal spray version of naloxone, a drug that reverses the effects of opioids, can save lives in a matter of seconds, according to Dr. Phil Skolnick, Chief Scientic Officer at Opiant Pharmaceuticals.

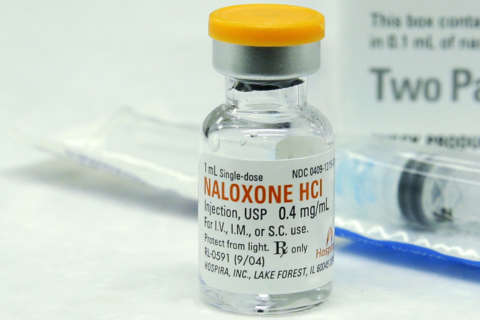

While naloxone has been approved to treat opioid overdoses for years until newer, more user-friendly forms of the drug were approved within the past five years, the means to administer it were limited.

Skolnick says only someone skilled at injections could administer the drug in the event of an opioid overdose.

That was before the naloxone spray, Narcan, was approved in 2015 and marketed in 2016.

The idea came about years before, around 2012, when people were using “improvised naloxone devices” that sprayed naloxone into the nostril.

However, Skolnick, who has more than 45 years of pharmaceutical experience with a background in drug abuse, says there were flaws to this makeshift method of administering the drug.

“Most of the naloxone that was atomized into the nostril ended up down your throat or dribbling out your nose,” Skolnick told WTOP. “The second issue is when you use that device, you weren’t getting high enough blood levels, below the minimum recommended dose of naloxone.”

The feat, then, was to develop a concentrated formulation of naloxone, says Skolnick.

There are currently three FDA-approved means of administering naloxone: through a syringe/injection, with an auto injector known as Evzio and now the nasal Narcan spray, which enters the bloodstream as quickly as an injection.

What sets the nasal spray apart from the auto injector?

It’s much simpler to use, says Skolnick.

Evzio, the auto-injector that was approved in 2014, “comes with a training device that talks you through it.” In essence, it’s like an EpiPen for opioid overdoses.

Skolnick says the nasal spray, which comes without a training guide is “intuitive and easy to use.”

And while the accessibility to this medicine is good for schools, first responders and others that treat people while opioid addiction, Skolnick believes prescribing a naloxone product alongside opioid medication may be a way into tackling overdose deaths.

The CDC set out guidelines in 2016 recommending a naloxone prescription to patients with increased factors for opioid-related abuse. Vermont and Virginia have mandated co-prescribing naloxone.

“Co-prescribing is going to be more the norm than the exception, and I think that’s really important because that’s how lives are going to get saved.”

However, Skolnick is also aware of some of the criticism of naloxone: that addicts may continue to use once they know it can save their lives.

He argues that addiction is a “medical condition secondary to a habit,” and equates to saving an opioid abuser’s life to saving an obese person from a cardiac arrest.

“What you’re doing is saving a life, and you’re giving that individual the opportunity to perhaps seek treatment,” Skolnick said. “What is the solution to the opioid epidemic? One of them is when someone (has) overdosed, is rescued and brought to the emergency room, that they be referred to some sort of addiction treatment program.”

WTOP’s Michelle Basch contributed to this report.