Emerging Contaminants

- Endocrine distruptors

- Metals

- Organic compounds

- Toxic chemicals

- Prescription drugs

WASHINGTON – While area drinking water sourced from the Potomac River is safe for consumption, it is not treated for the known chemicals and pharmaceuticals contaminating the river — substances that cause concern among water quality experts.

The main pollutant to the river is still storm runoff, but thousands of different types of prescription drugs and chemicals from personal care products are growing in strength in the Potomac, from both human and agricultural waste.

What’s in the water?

While only trace amounts of these chemicals have been detected in the water, the amount of what the water quality industry calls “emerging contaminants” has increased in potency over the last two decades, according to the Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin.

“They are things like prescription drugs, various hormone products, caffeine from coffee. These are just sort of everyday products that people use and they pass through wastewater treatment plants,” says Carlton Haywood, executive director of the multi-state commission created to protect the Potomac watershed.

These chemical contaminants were not strong enough to measure in the water 20 to 30 years ago, Haywood says. Now, their presence in natural bodies of water is raising concern.

Despite the awareness of these chemicals in the water, there is no health requirement that drinking water must be treated for pharmaceutical contamination, confirms Tom Jacobus, general manager of the Washington Aqueduct.

The aqueduct provides drinking water to the District, Arlington County and the city of Falls Church.

Some residents are worried about the presence of drugs and chemicals in the river.

“I don’t drink the water in D.C. without a Brita,” says college student Trisha Michelson, who lives in D.C.

Ten years after their discovery, the prevalence in the Potomac of intersex fish — fish with characteristics of both sexes — also continues to raise concerns. The latest research indicates a high correlation between intersex fish, the herbicide atrazine and a pesticide called trans-Nonachlor.

But a number of unanswered questions remain about the chemicals in the river and their effects on the overall health of the water.

“It’s a big city, (so) nobody knows what’s being dumped in all points in the river,” says Alex Caraballo, a resident of Falls Church.

Despite the concern, the World Health Organization has deemed the worldwide problem of drug-contaminated natural waters tenable. Jacobus agrees that the chemical contamination is not a present threat to the health of the area’s drinking water.

“[Intersex] fish live in the river, (but) we drink the river. There’s a difference,” Jacobus says. “The physiological basis of a fish system and human system are different. Nevertheless, we are interested in working with scientists, with the EPA and the American Water Research Foundation to look at the advances.”

In its 2012 study on the potential health effects related to pharmaceuticals in the water, the WHO found that in most cases the level of pharmaceutical contamination was lower than a “therapeutic dose,” and that “adverse impacts on human health are very unlikely at current levels of exposure in drinking water.”

While the WHO did not find cause for concern, there are no conclusive findings about the long-term health effects that the chemicals might cause.

Contamination of the Potomac

Locally, contaminants such as pharmaceuticals coming through the Washington Aqueduct measure at “very, very low concentrations,” Jacobus says.

But he acknowledges that consumer concerns and industry advances could mean a change in the three-step sedimentation, filtration and treatment process currently in place at the Washington Aqueduct.

In preparation for that possibility, the aqueduct is conducting its Future Treatment Alternative Study to find other ways to treat the water if stricter standards are put in place.

Current treatment methods eliminate 50 percent of most pharmaceuticals from drinking water, according to the WHO report. But to get 99 percent of drugs out, the WHO says stronger treatment is necessary.

“If we had to start treating for very, very low levels of pharmaceuticals, we would have to add additional treatment processes — perhaps ozone or UV or certain kinds of micro-filtration,” Jacobus says.

Changing the current system would be expensive. The cost of upgrading filtration and treatment facilities and adding chemicals would trickle down to consumers, Jacobus says. But he does not foresee any changes to regulations coming in the next few years.

The far cheaper and easier fix: Keep the drugs out of the water in the first place.

“If you flush those things down the toilet … they’re going to go to the wastewater treatment plant, and straight through the wastewater treatment plant into the river,” Haywood says.

Caffeine is one of the most prevalent chemicals found in the river. It is an ingredient in several over-the-counter medications, according to the Environmental Protection Agency’s research on pharmaceuticals and personal care products in natural waters.

Haywood points out that most studies on the health effects of these products in drinking water do not take into account the combination of multiple chemicals.

“Scientific studies typically take one compound and look for the effect of that on organisms, but they don’t take a look at a soup of many different compounds mixed together,” Haywood says. “So we don’t know that they’re a problem, but we know they’re out there.”

A question of testing

While the EPA is conducting studies on the presence of emerging contaminants in natural waters, it does not regularly monitor contamination levels.

“Regarding the pharmaceuticals, (the) EPA and the states generally do not perform ambient water quality monitoring,” says David Sternberg, spokesman for the EPA.

The U.S. Geological Survey is starting to collect data on contaminants in rivers and streams, according to the EPA, and is working with local jurisdictions to share information from water quality readings.

But Jacobus says developing a system to identify the chemicals is an uphill battle.

“There are literally tens of thousands of pharmaceuticals, and the EPA is struggling to regulate categories of them and to determine what the human response effects are. At what level is there a threat?” he says.

It’s not clear whether these emerging contaminants were there all along, masked by other pollutants such as sewage, or whether they are increasing in potency, says Haywood.

Emerging contaminants include but are not limited to endocrine disruptors (hormones), metals, organic compounds, toxic chemicals and drugs.

“I think people would quickly recognize that many of these compounds are dangerous at high concentrations,” Haywood says. “What they may not recognize is that these compounds may be harmful to the environment at very low concentrations.”

If a lot of people use chemicals in small amounts every day, it turns into a more potent problem, he says. That concept is why the problem is so widespread.

“There is a general consensus that anywhere monitoring for these materials is done, at least trace amounts of many of them are likely to be found,” says Sternberg.

Though researchers have sampled the river and found trace amounts of chemicals, the Potomac is not monitored for the level of emerging chemicals. It is not required to be, according to the District’s Department of the Environment (DOE).

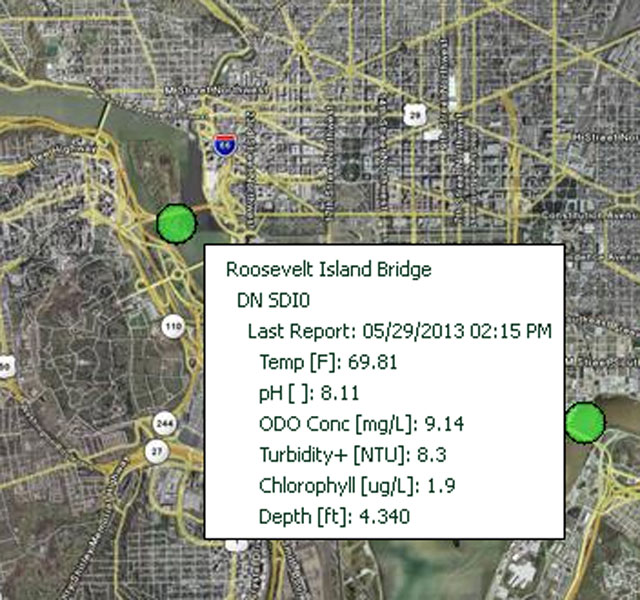

The Potomac River is sampled for water quality on a monthly basis. See the latest water quality readings here.

The department does offer real-time water quality monitoring of the river on its website, measuring temperature, pH and turbidity. But the monitoring tool does not show bacteria or E. coli levels.

The city is participating in the Potomac Source Water Protection Partnership to help ensure the safety of the city’s drinking water.

“We work together in trying to develop methodologies for monitoring data and analysis for emerging contaminants like personal care products, endocrine disrupters and so forth,” says Collin Burrell, associate director of the DOE’s Water Quality Division.

Is it safe to swim in the Potomac?

The Potomac River is currently listed as impaired for bacteria and is considered unsafe for swimming.

“I wouldn’t encourage anyone to go out there and swim,” Burrell says.

The river is tested monthly for bacteria. At its last reading, E. coli levels landed well within EPA standards. But those levels have to remain consistent for officials to lift the swimming ban.

“Most urban rivers have challenges with respect to water quality because of the very nature of urbanization — not only overflow, but stormwater runoff and other kinds of discharges to the river,” Burrell says.

As an older city, one-third of Washington, D.C., is served by a combined sewer and stormwater system.

The District’s Department of Environment measures fecal coliform in the water. The city’s assessment of the bacteria in the river, published in 2004, outlines more specifically where the contamination is coming from.

“Although the District of Columbia and the City of Alexandria have the combined sewer systems in the watershed, water quality analyses indicated that storm sewer loads are a significant source of fecal coliform,” the report says. “As a result … loads from upstream and other tributary sources contribute significantly to the bacteria problem in the Potomac River.”

Tributaries of the Potomac

␎

Battery Kemble Creek and Foundry Branch watersheds are within the District’s city limits. The Dalecarlia Tributary starts in D.C., but then crosses into Maryland before discharging into the Potomac River.

Maryland’s Department of the Environment oversees the majority of the river and monitors its safety.

“If you choose to swim in the natural waters, choosing sites in less developed areas with more water circulation is safer,” says Jay Apperson, spokesman for the Maryland DOE.

The higher presence of bacteria in the Potomac means an increased health risk, specifically to individuals with any open cuts, scrapes or wounds.

“Bacteria, parasites and algae can infect open wounds, but if the swimmer is healthy, there are basic preventative steps to take when swimming to have a problem-free visit to the water,” says Matt Skiljo, waterborne pathogens control program coordinator for the Virginia Department of Health. “If you’re going to go swimming in natural water, look for any advisories in the area. Avoid swallowing the water. Don’t swim if you’re ill or have an open wound.”

Related Stories:

- Herbicides likely source of growing intersex fish problem (Video)

- Fisherman’s perspective: Effect of snakeheads and Potomac River’s health (Video)

- How Blue Plains treats wastewater

- Anacostia River: Ugly duckling or blossoming flower? (Video)

- Troubled Waters: About this series

- More Troubled Waters

Follow @WTOP on Twitter.