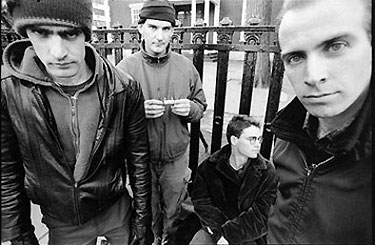

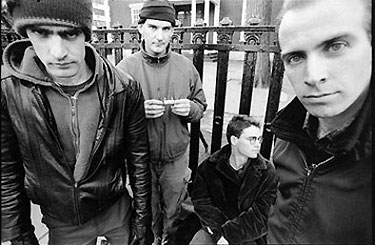

ARLINGTON, Va. — If you were able to catch Fugazi in its prime from 1987 to 2003, you witnessed shoving, spitting and screeching. Its live shows were nothing if not visceral testaments to the spirit of DIY.

It’s been about seven years since the local post-punk legends played their last show and went on an indefinite hiatus. But thanks to the herculean efforts of Dischord Records — a label that is home not just to Fugazi, but to the D.C. punk scene at large — more than 800 live recordings can be downloaded onto your computer for as little as $1.

From its inception, the D.C. band defied commercial branding and kept ticket prices to just $5 for a simple reason.

“The point of music is to be heard,” singer Ian MacKaye says. “Music will happen no matter what.”

Practically anyone could listen to MacKaye and company tell the crowd about everything that was wrong with the world. From broken social promises to ingrained sexism, it was like a crash course in anti-establishment politics.

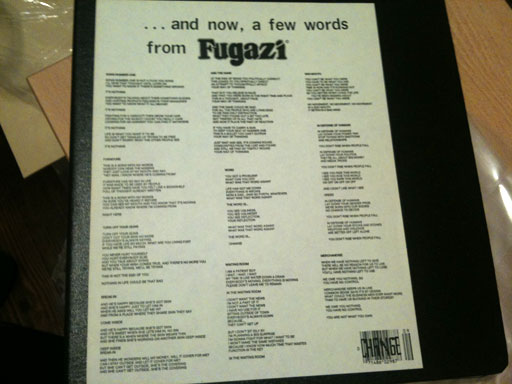

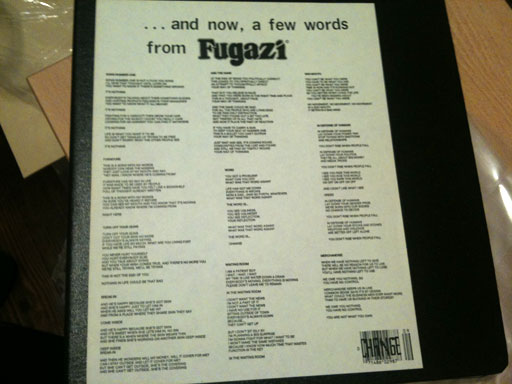

That spirit continues to roar in the Fugazi Live Series, officially launching Dec. 1. The exhaustive project includes everything from downloadable live recordings — 130 to start, with an additional 25 being added each month — to photos, fliers and band notes available to fans online.

“This is daunting,” MacKaye says. “We are daunted. It’s so much material to upload and keep track of.”

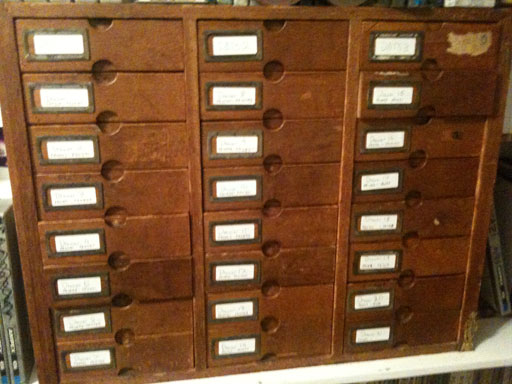

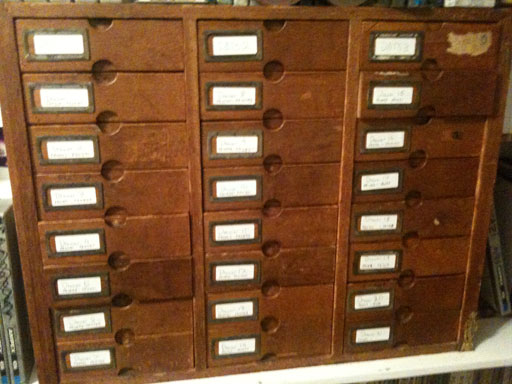

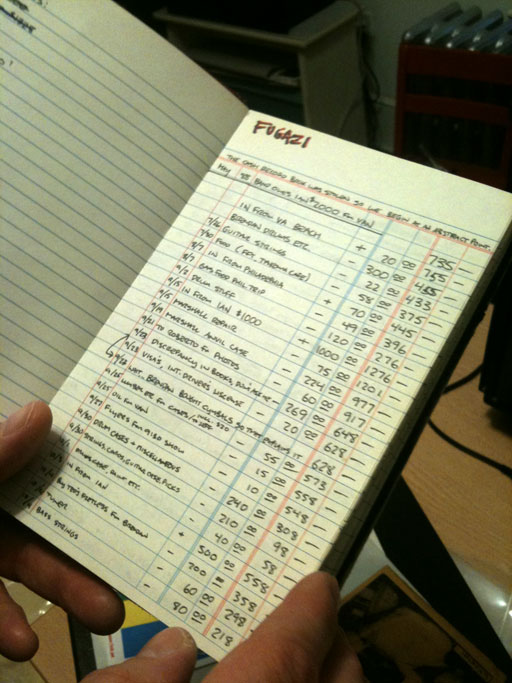

This archiving process appears to be MacKaye’s specialty.

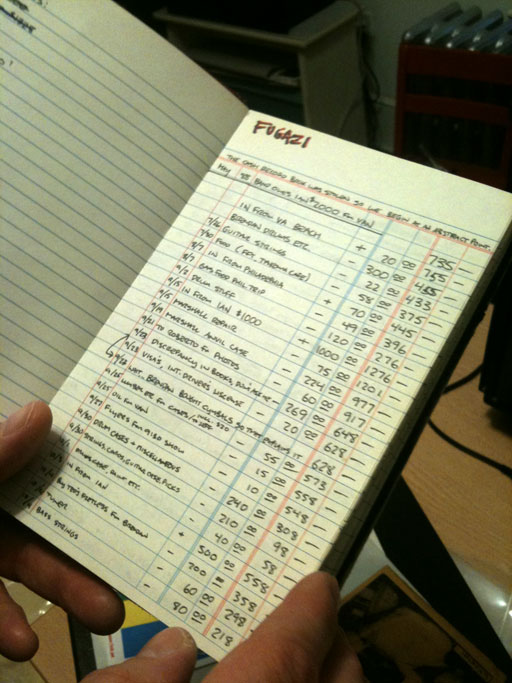

The Dischord house and label, both situated nondescriptly in Arlington, Va., act as living, breathing museums of the band’s history. Cassettes and reels methodically line an upstairs bedroom, kept under lock and key at all times. An impressive cataloging system features all the necessary information for each show — date, location, set list. In separate notebooks, MacKaye meticulously jotted down even more information such as how many people attended a concert and how much money the band spent.

It has taken two full years just to get the first leg of the live project up and running. The intensive process goes something like this: create an online digital database to store all the files, make a master itinerary of all shows and songs, digitize each concert song by song, master each performance and then edit it, turn it into mp3s and upload it online.

It doesn’t end there.

Despite MacKaye’s painstaking record keeping, he was bound to miss something from the more than 1,100 shows played by Fugazi. Enter the fan. People can submit their photos and recordings to Dischord and have them featured in the live series. Users can also leave comments on each show, like the guy who remembers breaking his back in Buffalo, N.Y.

This back and forth is what makes the project so special. Not only do fans get to relive some of their favorite shows, Fugazi gets to revisit its past.

Perusing through the online catalog, MacKaye comes across a 1990 Dallas show. He remembers it because it was so different than any other concert he ever played.

The show was supposed to take place in a warehouse, a makeshift venue deemed unfit by the fire marshal. More than 700 people showed up, but the local police department insisted on shutting it down because of safety concerns. Fugazi employed the help of the crowd to paint fire lanes and write exit signs. It was still a no-go.

A compromise was made and a fence erected, literally. Police allowed the band to play from inside the warehouse while the crowd gathered outside in the street to hear the music. Naturally, a riot nearly broke out. Someone started a fire. Others jumped off the fence and into the jubilant horde. Fugazi played a full set like that and thanks to the series, everyone can experience that night.

Purists will notice fluctuations from song to song, performance to performance. Live, Fugazi allowed for a certain amount of improv on stage. Some sets were longer, or shorter, than others even if the band played the exact same songs.

“This is by and large for people who give a damn,” MacKaye says. “If you’re a connoisseur, you will hear lots of different versions [of the songs]. You hear other approaches.”

With such an open system, MacKaye isn’t worried about people downloading his music and disseminating it for free.

“Music is a form of communication that predates language,” MacKaye says. “It’s much more important, much older, much more significant, than anything in this room. It’s deep. It can’t be stopped.”

Follow Alicia Lozano and WTOP on Twitter.

(Copyright 2011 by WTOP. All Rights Reserved.)