When Jane Gilbert was appointed last summer as Miami-Dade County’s first “chief heat officer” — and the first in the country — she was charged with a seemingly impossible task: raise the public’s awareness about the dangers of extreme heat to the same level as hurricanes.

Gilbert said most of Miami’s previous climate-related work was centered around adapting to rising sea level, higher storm surge and flooding — but it was rarely about extreme heat.

“Heat was not a big focus,” Gilbert told CNN. “I ended up putting it into the city of Miami’s climate-ready strategy, because when I did neighborhood-level outreach on our planning process and was really drawing out what people’s biggest concerns were related to climate change, extreme heat and the compound risks of extreme heat with hurricane came up a lot.”

Heat already kills more Americans than any other weather-related disaster and the climate crisis has been making these extreme events more deadly. Heat deaths have outpaced hurricane deaths by more than 15-to-1 over the past decade, according to data tracked by the National Weather Service. But unlike hurricanes, heat’s invisible nature does not evoke a sense of urgency in the public mind.

Extreme heat is the “silent killer.”

Gilbert said cities have historically addressed the threat under the extreme-weather umbrella, tending to be overshadowed by strategies for floods, wildfires and sea level rise. So when a heat wave strikes, it wreaks havoc across infrastructure, health services, worker productivity, food production and disproportionately hits marginalized communities and low-income populations the hardest.

“There’s never been a role prior to this, where someone is solely focused on looking at the health and economic impacts of heat, and looking transversely not only across departments within that jurisdiction, so in my case within the county, but across agencies and across sectors,” Gilbert said. “I’m charged with breaking down those silos.”

As hot-temperature records outpace cool records, US cities more and more are looking to officers like Gilbert to address the crisis. After Gilbert’s appointment, Phoenix and Los Angeles followed suit, hiring their own chief heat officers in hopes of improving public awareness and the heat-vulnerable fabric of each city to protect lives.

“My role is to really better understand the risks — current and in the future, and secondly, engage community-wide stakeholders in forming solutions,” Gilbert said.

Heat islands and public health

The compounding consequences of urban heat don’t fall equally across communities. A recent study from the University of California, San Diego, found that low-income neighborhoods and communities with high Black, Hispanic and Asian populations experience significantly more heat than wealthier and predominantly White neighborhoods.

It reflects an earlier study that traces the legacy of neighborhood redlining, the government-sanctioned effort in the 1930s to segregate people of color by denying them housing loans and insurance. The research analyzed 108 cities in the US and found that 94% of historically redlined neighborhoods are disproportionately hotter than other areas in the same city.

This is because of the so-called urban heat island effect, which has made some urban communities even more vulnerable. Areas with a lot of asphalt, buildings and freeways tend to absorb a significant amount of the sun’s energy and emit it as heat. Areas with green space — parks, rivers, tree-lined streets — absorb and emit less.

“Heat is costing us so much,” Kathy Baughman McLeod, director of the Adrienne Arsht-Rockefeller Foundation Resilience Center, the group leading the appointment of chief heat officers around the world, told CNN. “It is an infrastructure crisis. It’s a health crisis. It’s a social and equity crisis.”

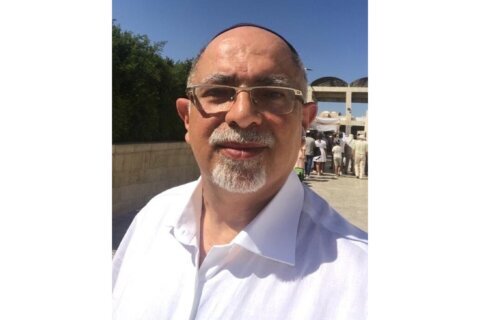

Phoenix has struggled with the heat inequality. In Maricopa County, houseless people account for the majority of heat-related deaths, according to David Hondula, Phoenix’s chief heat officer who was appointed late last summer.

But armed with this knowledge, Hondula has deployed staff and volunteers to alleviate the area’s homeless population and eliminate heat-related risks. This sparked an interagency partnership with Phoenix’s homeless services division, Hondula said. Each shift out on the streets, a case manager with the division would join Hondula’s team on the ground to help manage housing questions that Hondula’s team otherwise wouldn’t know the answer to — and he said it has made a huge difference in their approach.

“The other day, literally the moment we pulled in a parking lot, we were connected with a family of nine or 10 living out of their car, and because our case manager was there, by the end of our shift, they were all on their way to a shelter that evening,” he told CNN. “While we’re very happy to get cold water in people’s hands and let them know about cooling centers, these are the meaningful differences that will really pay off in the long term to keep people safe in our community.”

Marta Segura was appointed Los Angeles’ chief heat officer just four weeks ago, and she now faces a similar challenge. Because of the city’s widespread houseless population, she said it’s been difficult to come up with targeted and holistic solutions to protect them from extreme heat.

“Extreme heat exacerbates those [pre-existing health] conditions and stagnates pollution and smoke, and it’s why we see more deaths and hospitalizations in our most vulnerable communities that also have the least tree canopy and open space,” Segura told CNN.

Segura said these communities need more than shade and water. She said she plans to modify building codes to create more climate-adapted and resilient homes that would allow residents to be safe and cool during blistering heat waves.

From unhoused communities to babies and the elderly population, climate change will only put the most vulnerable people at even greater risk if cities fail to rethink the way cities are designed to adapt to heat, Segura said. Without sweeping measures, people in these areas would need to fundamentally change their way of life to adapt to more punishing heat waves.

With “rapid urbanization in cities and the exacerbation of the urban heat island effect,” Baughman McLeod said people are not prepared for rising temperatures. Nevertheless, cities also have the power to change that trajectory.

“In my opinion, cities have their hands on the levers that shape how hot cities and regions will be, how comfortable people will be in those cities and regions, but also the lever on many of the programs and strategies that can keep people safe when it is hot,” Hondula said.