This article originally appeared on WTOP.com on August 23, 2013.

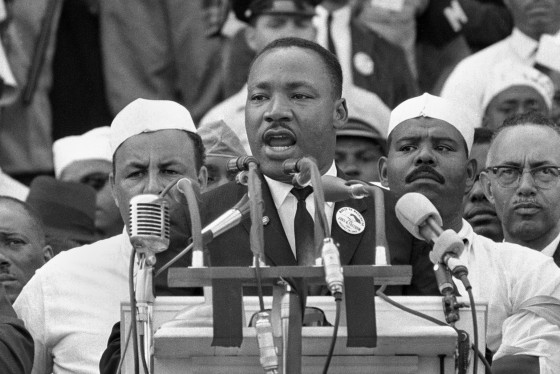

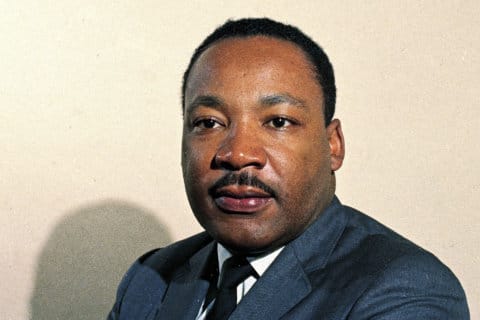

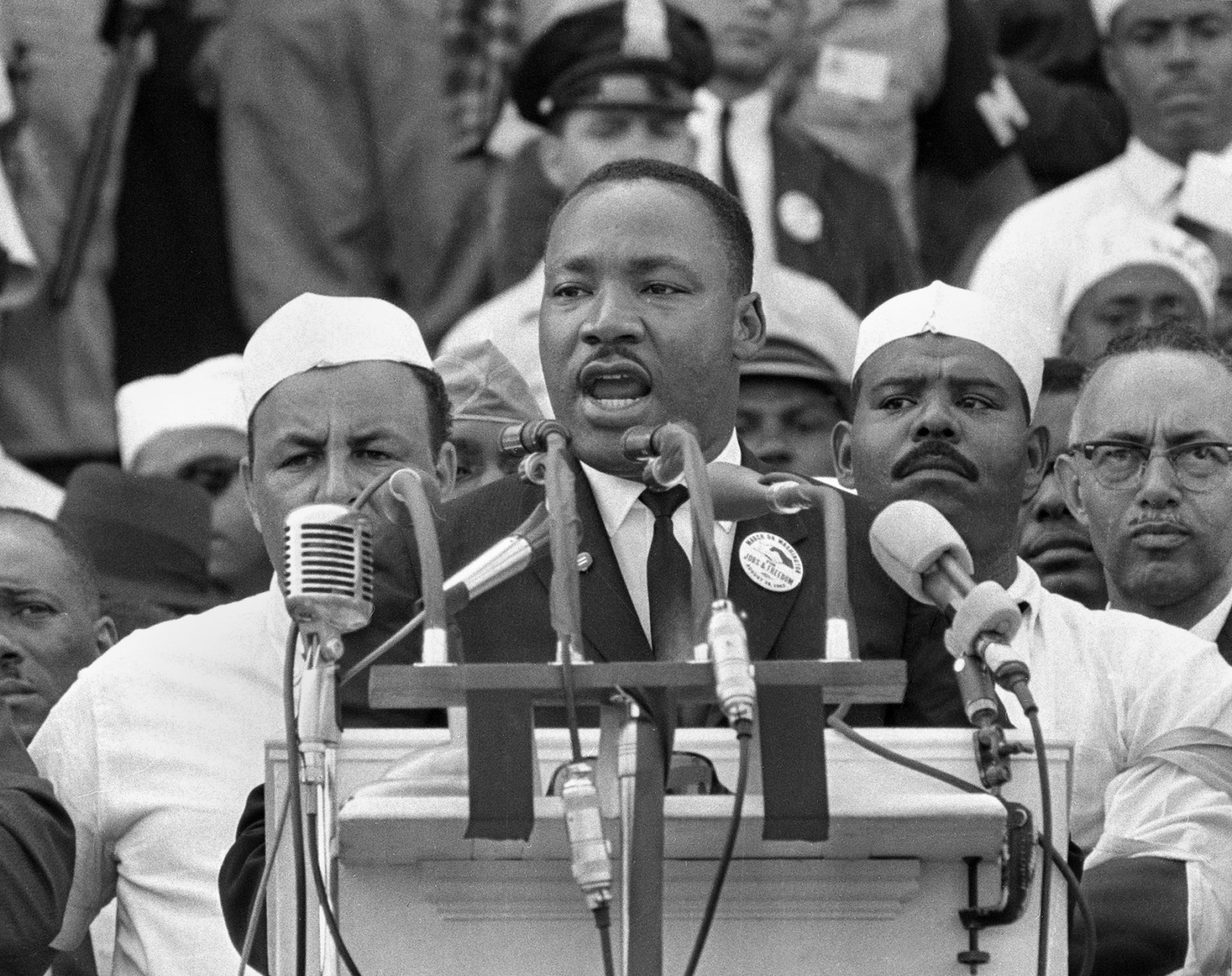

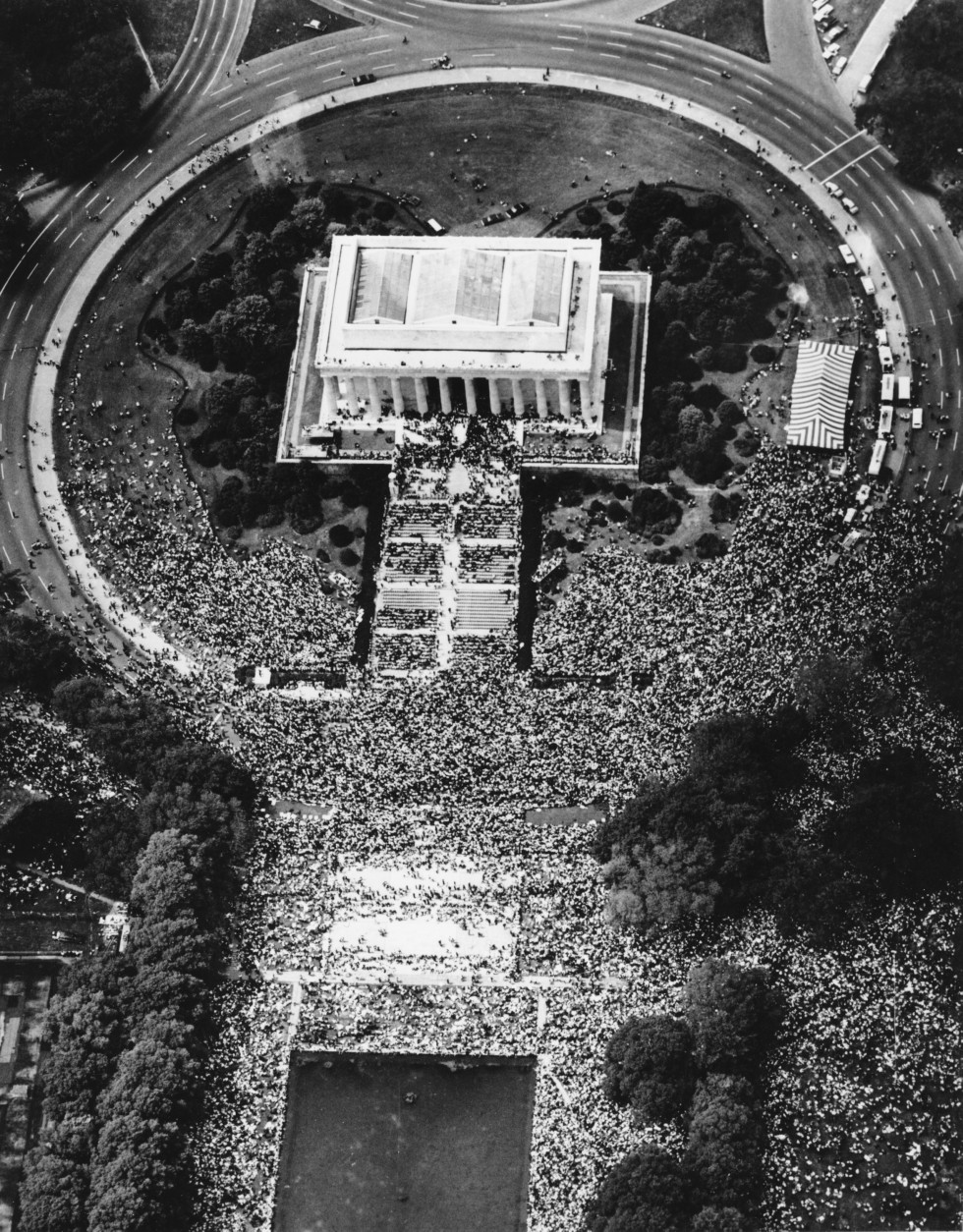

WASHINGTON – If not for two spontaneous, subtle, impeccably-timed acts, the iconic phrase “I Have a Dream” delivered by Martin Luther King Jr. on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial may have never been spoken.

Among King’s inner circle were two people he spoke with virtually every day: his attorney Clarence B. Jones and New York businessman Stanley Levinson. In early July, when it was clear the march would happen, Jones and Levinson met with King regularly and were tasked with drafting a framework for the speech.

“We felt that Martin had an obligation to provide leadership, offering a vision that we were involved in action not activity; a clear-eyed assessment of the challenges we faced and a road map of how we could best meet those challenges,” Jones, who also served as King’s draft speechwriter, wrote in his book, “Behind the Dream: The Making of the Speech that Transformed a Nation.”

The night before the march, in a cordoned-off area of the Willard Hotel lobby, a final meeting was planned to go over the final details of King’s speech.

According to Jones, along with he and King, the other attendees at the meeting were Cleveland Robinson, Walter Fauntroy, Bernard Lee, Ralph Abernathy, Lawrence Reddick and Bayard Rustin.

After a vigorous debate in which Jones took notes, he went to his hotel room and turned his notes into words King could recite. A short time later, he delivered his draft to King. As was customary in their relationship of speechwriter and speech-giver, King took the draft to tweak it and make his own. Jones didn’t see the final draft.

As King made his way through the first several paragraphs of the speech, Jones realized King had not changed a word he had written.

“What I was writing was not my original writing,” Jones says. “It was merely a summary of what we had discussed before. I had simply put it into textual form in case he wanted to use that to reference in putting his speech together.”

The question of when King would speak during the march was also a thorny one.

“That process was really as a result of taming egos,” says Jones.

After a series of meetings the week leading up to the march, it was decided King would appear in the middle of the program.

Jones wasn’t having it. In the middle of one planning meeting without King, he made his case for King to not only speak last, but to also speak the longest.

“I said you run the risk … that after he speaks a lot of the people at the march will get up and leave,” Jones says he told the group.

His plea worked.

“A. Phillip Randolph agreed with me, and Ted Brown and Bayard [Rustin], and so forth,” Jones says. “And, so it was agreed that [King] would be the last speaker.”

And, if needed, King would be given the most time for his speech.

By interrupting a single meeting, Jones had set the stage for history.

A preacher emerges

By 1963 Mahalia Jackson was already a legend in Gospel music. In 1950, she became the first Gospel singer to perform at Carnegie Hall. She sang at President John F. Kennedy’s inaugural ball in 1961. And before King took the stage to speak at the march, Jackson belted out the Negro spirituals “How I Got Over” and “I’ve Been ‘Buked, and I’ve Been Scorned.”

Jackson was also King’s favorite singer.

“When Martin would get low … he would track Mahalia down, wherever she was, and call her on the phone,” Jones writes in “Behind the Dream.”

Jackson had King’s trust.

She was also on the platform, sitting in the area of celebrities and dignitaries behind King, as he read from his prepared text:

Go back to Mississippi, go back to Alabama, go back to South Carolina, go back to Georgia, go back to Louisiana, go back to the slums and ghettos of our northern cities, knowing that somehow this situation can and will be changed. Let us not wallow in the valley of despair.

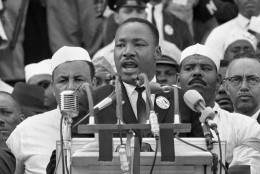

King paused for 10 seconds as the crowd cheered him on. During that pause, the trajectory of the speech, and its place in history, transformed.

Jones says he was about 15 yards behind King, when he heard someone from the stage yell out to King.

“Mahalia Jackson…she shouted to him, ‘Tell them about the dream, Martin. Tell them about the dream’,” Jones says.

King also heard it.

“His reaction to it was to look in the direction of Mahalia, but then to take the prepared text that he was reading and slide it to the left side of the lectern,” Jones says.

King had gone from lecturer to preacher.

“I turned to somebody standing next to me and I said, ‘These people don’t know it, but they’re about to go to church’,” Jones says.

King proceeded, and it was in that moment that the “dream” became reality:

I say to you today, my friends, so even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream.

The rest is history.

“From there on, that part of the speech that has become so celebrated as the ‘I Have a Dream’ speech was completely extemporaneous and was completely spontaneous,” Jones says.

King weaved his way through the remaining five minutes of the speech knitting together phrases and storylines culminating by a booming close in the spirit of the southern Baptist church world from which he was raised:

Free at last, free at last, Great God Almighty, We are free at last.

And even that line has a story.

“He had incorporated near the end some notes that he had made quoting in the words of an old Baptist preacher, ‘Free at last, free at last, free at last’,” Jones says.

Jones believes that while Dr. King’s speech immediately ascended into the rarified air of history-defining performances, the moment, aside from the words, in which it was given played a major role.

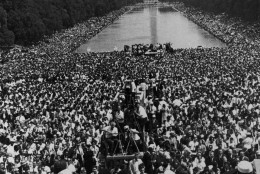

“The fact of the matter is that the overwhelming majority of people in America, white people particularly, had never heard or seen Martin Luther King, Jr. speak before. So, what you had that Wednesday, August 28, 1963, is that you had television pictures and the voice of Martin Luther King rebroadcast as part of the evening news in the top 100 television markets in the country. So, when the nation saw and heard this person speaking, they had as delayed reaction as I had when [the speech] was given. I was mesmerized.”

In order to protect King from being taken advantage of, Jones had the speech copyrighted. Though he faced a legal battle to have it upheld, the copyright is currently in effect until 2038.

Not even that process went smoothly. The speech was almost filed for copyright without a title. Jones was about to send the documents off to be filed with the speech titled “Martin Luther King’s Unpublished Speech of August 28, 1963.”

According to Jones, once it was pointed out to him that such a title wasn’t memorable, he changed it. With the white correction ribbon on his typewriter, Jones erased the black-typed ink, and above the line which read “Give the title of the work as it appears on the copies,” Jones gave the speech its proper name.

“I Have a Dream.”