A study of more than a quarter-million people in over 50 countries finds the links between musical preferences and personality are universal.

The University of Cambridge study of 350,000 people on six continents suggests people who share personality types often prefer the same type of music, regardless of where those people live.

For instance, Ed Sheeran’s “Shivers” is as likely to appeal to extraverts living in the United States as those living in Argentina or India.

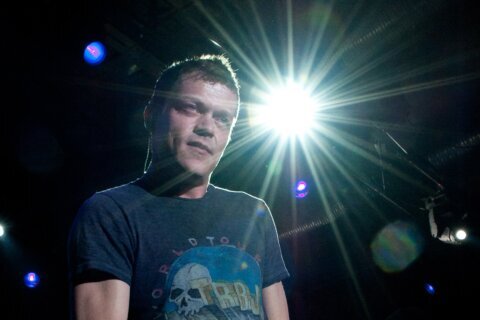

Likewise, a person with neurotic traits will typically respond favorably when hearing “Smells Like Teen Sprit” by Nirvana, regardless of where the listener lives.

The research was led by Dr. David Greenberg, an honorary research associate at the university’s Autism Research Centre. Greenberg hopes the findings shows the potential of using music as a bridge between people from different cultures.

The study, published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, utilizes the five widely accepted personality traits — openness, conscientiousness, extroversion, agreeableness and neuroticism.

Across the world, without significant variation, researchers found the same positive correlations between extroversion and contemporary music; between conscientiousness and unpretentious music; between agreeableness and mellow, unpretentious music; and between openness and mellow, contemporary, intense and sophisticated music.

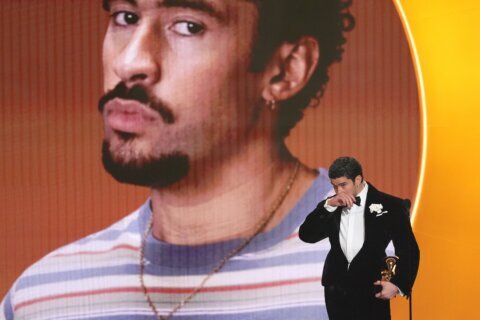

According to Greenberg, agreeable people the world over will tend to like Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On,” or “Shallow,” by Lady Gaga and Bradley Cooper.

Open people, regardless of where they live, would likely respond well to hearing David Bowie’s “Space Oddity,” or songs by Nina Simone.

The researchers found extroversion, which is defined by excitement-seeking, sociability and positive emotions, would be positively associated with contemporary music, with its upbeat and danceable features.

Similarly, people who identified as conscientious, which is associated with order and obedience, often were at odds with intense musical styles, which are characterized by aggressive and rebellious themes.

When it came to neuroticism, Greenberg expected participants would either preferred sad music to express their loneliness or upbeat music to shift their mood.

“Actually, on average, they seem to prefer more intense musical styles, which perhaps reflects inner angst and frustration. That was surprising, but people use music in different ways — some might use it for catharsis, others to change their mood,” Greenberg said.

Greenberg and his colleagues used two different musical preference assessment tools. The first asked people to self-report the extent to which they liked listening to 23 genres of music as well as completing the Ten-Item Personality Inventory — or TEPEE — and provided demographic information.

The second method involved asking participants to listen to short audio clips from 16 genres and give their preferential reactions to each.

Greenberg said the study does not attempt to pigeonhole music-lovers, and acknowledges “musical preferences do shift and change, they are not set in stone.”

He hopes the research will encourage looking at the unifying possibilities of music: “People may be divided by geography, language and culture, but if an introvert in one part of the world likes the same music as introverts elsewhere, that suggests music could be a very powerful bridge.”