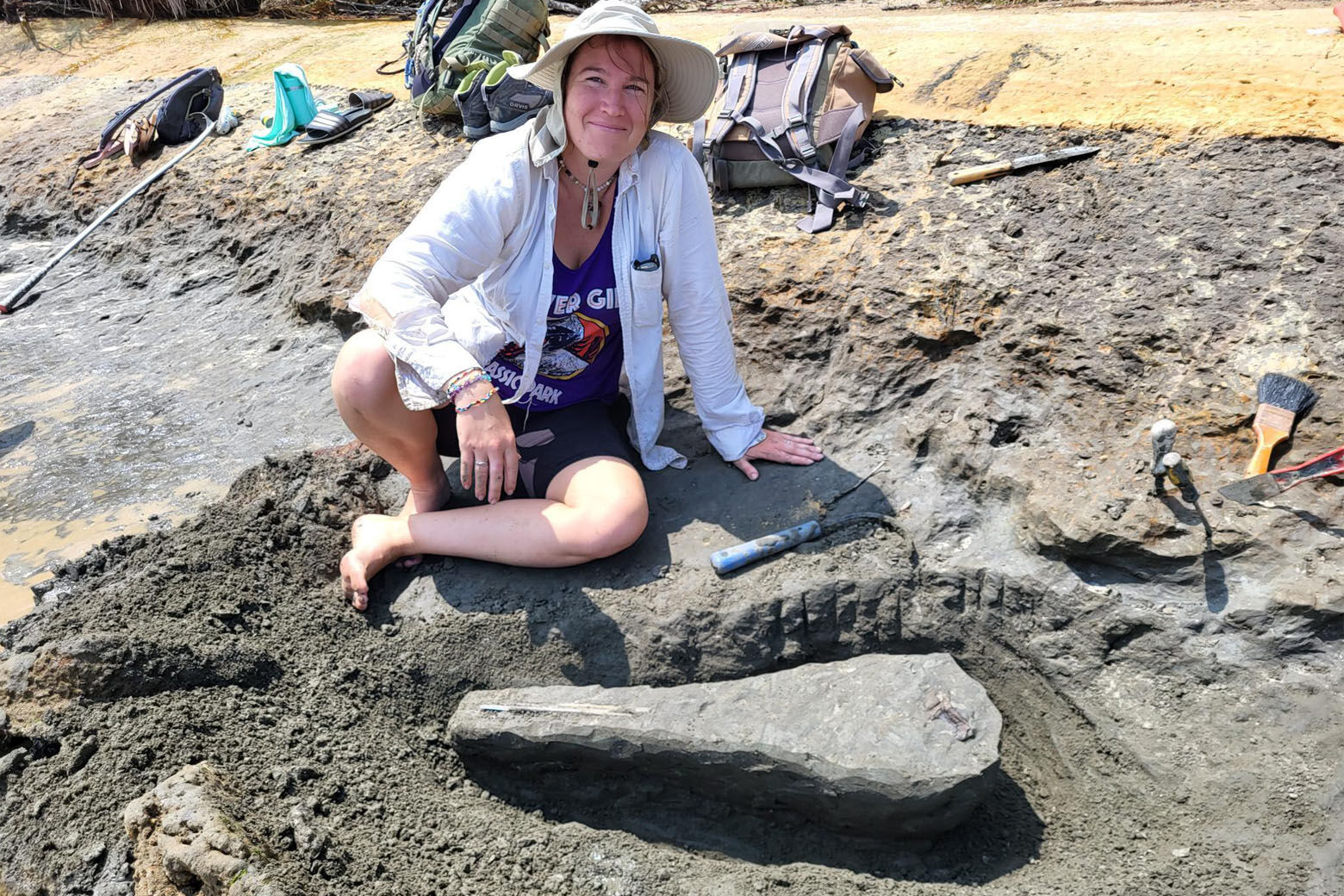

On Saturday night, Calvert Marine Museum volunteer Emily Bzdyk was collecting fossils at Calvert Cliffs in Maryland when she made a discovery that could help write history books on marine life from long ago: In the beach, the water and surf uncovered a 15-million-year-old dolphin skull.

“Rarely are they in this good of condition,” said Stephen Groff with the Calvert County Marine Museum.

It is not uncommon to find fossils from marine mammals. Dolphin skulls are typically found twice a year in southern Maryland. But this find, according to Groff, stands to be the most intact of the finds. It could also turn out to be a species that was previously not known about.

Bzdyk’s discovery led to Groff and others joining her on Sunday for a dig at the beach to unearth the skull. It is a process that takes patience and precision to not damage the fossil. Once removed from the sand, the skull was taken by boat to the museum.

Now, it is in the process of being dried. When wet, glues and other material used to preserve fossils cannot be used. Next, work to carefully remove remaining sediment will take place.

Bzdyk will be in charge of that process.

“It’ll probably take her a few months, takes several dozen hours to completely clean one of these skulls because we have to be very careful that we don’t break anything or cause any damage,” Groff said.

While work is done, museum visitors will be able to see Bzdyk conduct the work in the coming weeks.

Groff said one misconception is that all fossils found in the area are found in the cliffs. But some are found in the beach like this one was.

During the Miocene period, when the marine mammal swam the earth, the sea level was much higher, according to Groff. What is the beach now was once the ocean floor. Now, as the ocean is eroding away part of the beach, more fossils are being uncovered.

Groff said while the term dolphin is used, the species of marine mammals didn’t look like bottled nose dolphins.

“You can kind of think of them like a modern swordfish, or sailfish,” Groff said. “They have a long snout, they probably use it to club fish just like modern a billfish do, or to maybe probe around in the mud on the seafloor to stir up fish,” said Groff.

Groff said there is a good chance this isn’t a new species, but only a full exam of the fossil will tell. That said, he does suspect there are more species that have yet to be discovered, since it is believed during that time that 40 toothed marine mammals lived in the area.

Groff said it is discoveries like this that has him looking forward to coming to work each day.

“To be able to go out in the field and, you know, recover and preserve a piece of our local natural history, it’s just wonderful. I can’t describe how exciting it is,” he said.