ANNAPOLIS, Maryland — Halloween is known as one of the spookiest times of the year, filled with witches, ghosts, and scattering bats. But Maryland’s flapping, black creatures may be less prevalent this year, like years in the recent past.

From cold-loving fungus to high-powered wind turbines, Maryland’s bats have been getting annihilated.

The decline of the Maryland bat population

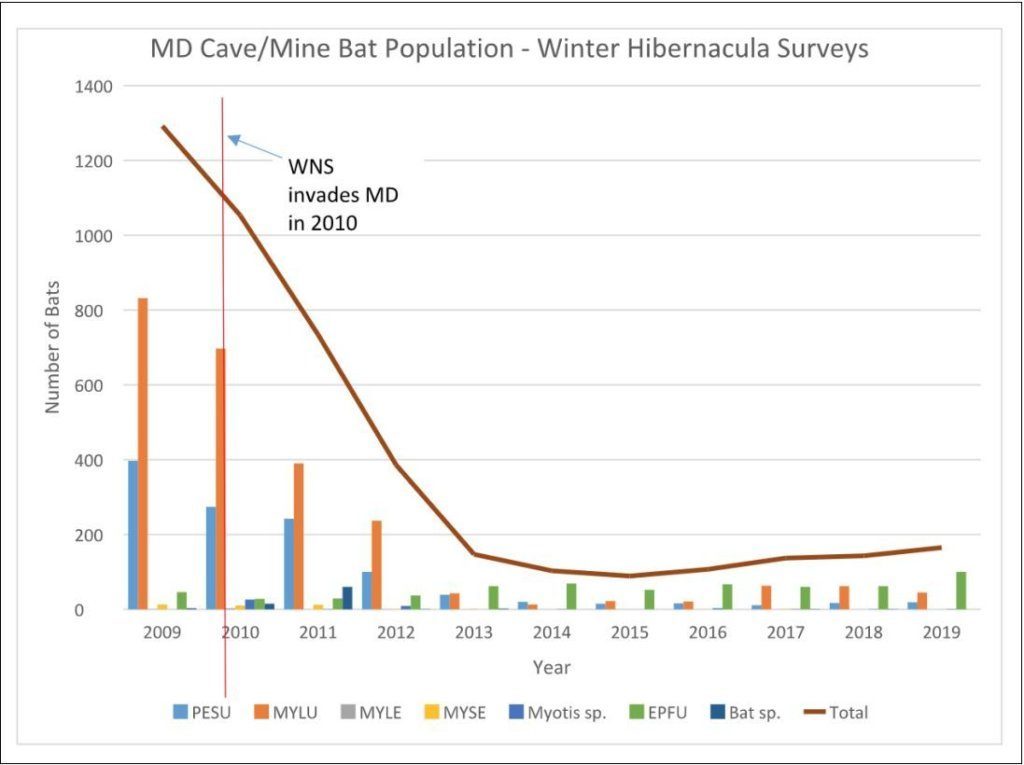

Maryland’s bat population has been decimated by white-nose syndrome since its first documentation in Allegany County in 2010.

White-nose syndrome is a disease caused by a fungus that affects hibernating bats. The fungus grows on the bats, irritates them, and can wake them up during hibernation, said Dana Limpert, eastern regional ecologist at the Maryland Department of Natural Resources.

Once awake, the bats use up their fat reserves and go hunting for insects at a time when there are none for them to eat. The bats starve and die, Limpert said.

Hibernating bats are affected the most because white-nose syndrome is a “cold-loving fungus,” Feller said, and does well in caves and mines where bats hibernate.

White-Nose Syndrome has killed more than 5.7 million bats in the eastern United States since its appearance, according to the Maryland Department of Natural Resources.

The fungus was discovered near Albany, New York, in February 2006, and quickly spread throughout the northeast, according to the White-Nose Syndrome Response Team, a national coalition of scientists and others. White-nose syndrome first appeared in Maryland between 2009 and 2010.

Once the syndrome arrived in Maryland, there was a “precipitous drop in white-nose syndrome species,” Limpert said. There were no bats found in some caves and mines.

There has been a 90-99% decline in some bat species in Maryland, according to Daniel Feller, western regional ecologist at the Maryland Department of Natural Resources. Maryland is home to 10 species of bats, according to the department.

“To find a colony over 50 is a rarity now,” Limpert said.

The Northern long-eared bat is listed as threatened both federally and statewide. The Indiana bat, less common in Maryland, is also listed as endangered both federally and statewide. Although not listed, the state’s other hibernating bats — specifically, tri-colored, little brown, big brown — are not managing any better.

Maryland bats, specifically migrating bats, have also struggled due to the increase in wind farms.

Because bats are blind and utilize echolocation to fly around, they are not good at judging the speeds of the wind turbines, Feller said. As a result, they accidentally fly into the turbines and die.

The turbines can also lead to barometric trauma deaths in bats, Limpert said. The bats are attracted to the turbines but experience a sharp dip in pressure that causes their internal organs to explode.

Wind farms have become a “significant source of mortality” for migratory bats, Feller said.

Bats may just be scary to some, but they have a large impact on agriculture.

Gary McCracken, head of the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, estimated the loss of bats costs the national agricultural industry approximately $23 billion per year, with low estimates at $3.7 billion per year and high estimates at $53 billion per year.

What is the state doing to help the bats?

All hope is not completely lost, though. Feller said they are seeing some minor signs of improvement for the bats.

At one monitoring site, Feller had not seen a single bat in eight years. Last winter, three tri-colored bats (a species significantly affected by white-nose syndrome) were found. In other places, Feller said, populations are still low but appear to be stabilizing.

New research also indicates that coastal bats may fare better than inland bats, Limpert said, but this is still being studied in Maryland. The coastal bats of Long Island, New York, and Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts, have overwintered in crawl spaces in houses, rather than caves and mines, and appear to be doing better, Limpert said.

The state is taking precautions to reduce the spread of white-nose syndrome in caves. Bat gates have been put in place to protect the bats from people going into their areas of hibernation, Limpert said.

Additionally, researchers follow a decontamination protocol before entering a cave in case they came into contact with White-Nose Syndrome in a different location.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service recommends that all dirt and sediment be removed from clothing, shoes and equipment and all exposed equipment should be contained in sealed bags. Clothes should be changed and laundered at 131 degrees Fahrenheit for at least 20 minutes. Equipment should be cleaned and treated with chemical solutions if possible.

Research is being done around the country to find a cure for white-nose syndrome. Ultraviolet light has been shown to kill the fungus, Feller said, and the bats may be gaining some natural resistance to it.

However, bats are slow to reproduce, so they will be slow to recover.

Typically, bats only give birth to one bat pup in a given pregnancy, although some species have given birth to up to six, Paul A. Racey and Abigail C. Entwistle wrote in “Reproductive Biology of Bats.”

Additionally, wind companies have been willing to work with Feller and are turning off the turbines during periods of high migration, specifically during the nighttime hours in the fall, Feller said.

Can the public help?

The public can play a role in aiding the bat population as well.

If a bat is found in an attic or around the house, do not kill it and do not make contact with the bat. Rather, check out Maryland’s Department of Natural Resources website for protocol. A bat removal expert can be called to help extract the bat.

To avoid future bats entering the house, there is a bat exclusion process — explained on the Maryland Department of Natural Resources’ website — which will close up the holes that the bats use to get in. However, this process must be done during a certain time of the year to make sure that no bats get trapped inside.

For bat lovers and landowners, bat roosting boxes can be purchased to house bat colonies. The roosting boxes have been found to be extremely effective and are a great place for bats to live and raise their young, Feller said. Boxes should be within a quarter mile of water and 20-25 feet from the nearest trees. Roosting boxes are available on Amazon for as little as $30, or there are instructions to build a box on the Department of Natural Resources.

Keeping bats as pets will not help the bat population grow. Not only are they illegal in the state of Maryland, according to Anne Arundel County Animal Care & Control, but it shortens the bat’s lifespan.

According to the website for the Bat World Sanctuary, in Weatherford, Texas, bats can survive up to 25 years in the wild but rarely live longer than a year as pets.

Getting a bat as a pet is “a total waste of life as well as the $800 to $2,500 you spent on having a ‘cool’ pet,” according to the sanctuary’s website.