Although organizers of Woodstock 50 decided to cancel their scheduled “3 days of peace and music” at Merriweather Post Pavilion, 14 miles away, it’s Woodstock every day.

John Warden’s guitar workshop, Warden Custom Guitars, is located next to the barn, on his property in Woodstock, Maryland — population 6,986 — in Howard County, near its border with Baltimore County.

“Woodstock was the first stop for fuel, when steam locomotives were powered by wood,” said Warden. “So, there’s always a Woodstock around most major metropolitan cities.”

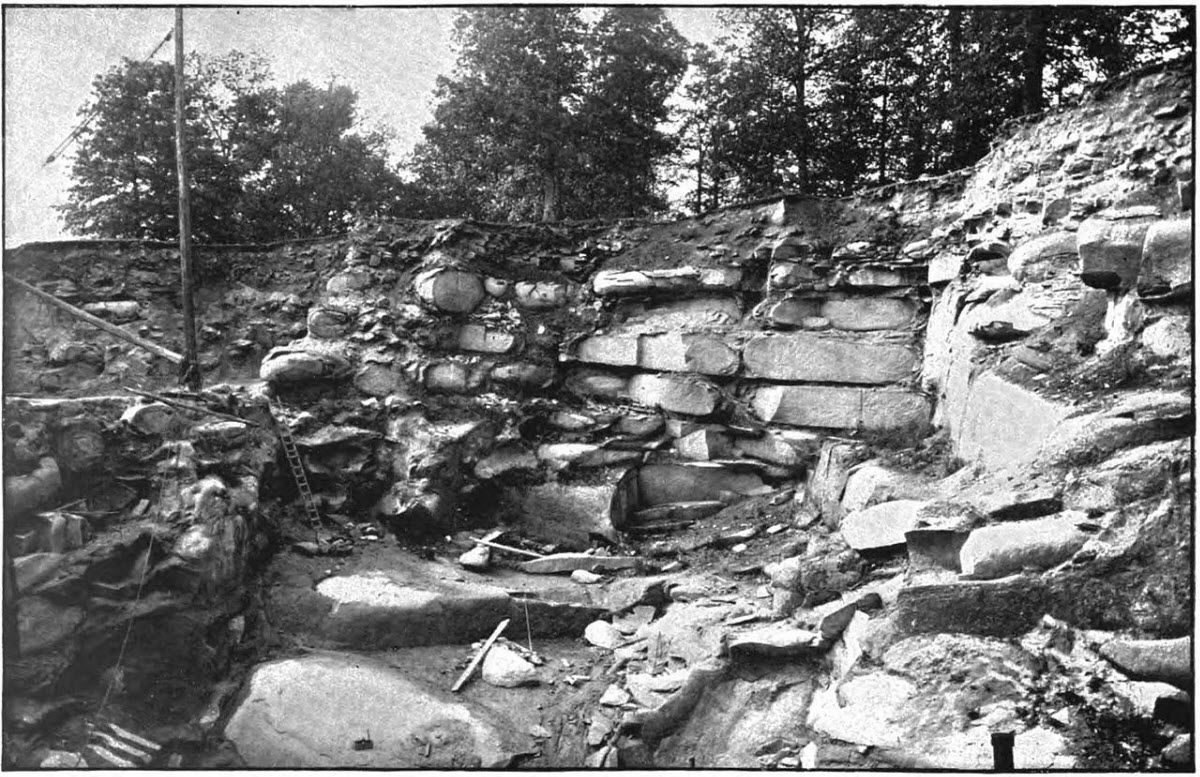

The B&O Railroad station in Woodstock, Maryland, was built in 1835. Granite quarries in and around Woodstock, including in the adjacent town of Granite, produced quartz used in the Library of Congress.

Warden, 66, began building and repairing guitars when he was 16 — about the same time as the original 1969 Woodstock festival, in Bethel, New York.

Over the years, he’s been entrusted with repairing the acoustic instruments of some of the world’s best guitarists, ranging from classical virtuoso Andres Segovia to Nils Lofgren, the Bethesda-raised guitarist, best-known for his work in Bruce Springsteen’s E Street Band.

But, early in his career — somewhere between 1972 and 1975 — Warden made his first connection with Woodstock.

“When I was in Columbus [Ohio], I worked on a [Martin] D-28 that Stephen Stills bought from Columbus Folk Music,” Warden said. “I was prepping it for sale.”

Stills’ acoustic guitar-playing during Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young’s “Suite: Judy Blue Eyes” is regarded as one of the highlights of the 1969 Woodstock.

“It needed a neck reset and a new bridge,” Warden said. “He had played the guitar before it had the work done, and the sale was contingent on having the repairs done.”

Though memories and stories differ about precisely which guitar Stills played during the original Woodstock, Warden has no problem remembering the Stills guitar he fine-tuned. “It was a Brazilian rosewood D-28, that was about a 1947 or ’48, and it was in really good shape,” he recalled.

In a workshop stocked with partially disassembled guitars and banjos, and power tools, files and lasers designed to make minuscule improvements in how well an instrument can be played, Warden reflects on his interaction with Stills and other musicians in the ’60s and ’70s.

“This goes back to when artists actually bought their own guitars,” Warden said. “Most people that were an artist bought their own guitar, they didn’t get one given to them” by a guitar company, as part of a sponsorship.

In the remote farm setting, and despite his obvious love and appreciation of music, the only sounds in his workshop are the humming of equipment and the rasp of infinitesimal particles of wood being shaved to perfect a guitar’s feel.

“I have a hard time working and listening to background music, because I pay attention to the music,” he said.

Asked if he adjusts guitars to meet musicians’ preferences, his answer borders on a scoff: “It’s either right, or it’s not. You can modify them to make them play toward somebody’s preferences, but if they’re right, that’s really a minor adjustment and easy to do.”

Like most people, Warden’s initial introduction to the 1969 Woodstock was from the film.

“I thought Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young had taken the style of music that I was really interested in and moved it forward — improved it,” he said.

Despite his connection with the original roots of Woodstock, Warden said he wouldn’t have attended the 50th anniversary show, despite its proximity. “I’m too old,” he said. “Maybe when I was 16 or 17.”

Warden believes musical acts would have been happy with their sounds in the amphitheater located in Symphony Woods.

“Merriweather Post Pavilion is a nice venue, and it’s someplace that could handle it well,” he said. “Whereas, a lot of places, I wouldn’t want to go see it.”

Despite Woodstock 50’s cancellation, his connection with the groundbreaking festival will continue.

“With my guitar repairing, having Woodstock in the address is appealing,” he said, with a wink.