Many who live in fast-growing Loudoun County, Virginia, may not realize populated developments were built on or near historically African American towns, villages, hamlets or neighborhoods.

Now, the county and Friends of the Thomas Balch Library’s Black History Committee are updating a survey to document the buildings, settlements, landscapes, cemeteries and burial grounds in these neighborhoods.

“I would say we’re now counting up to about 30 African American historic communities — some of which were established prior to emancipation, but most afterwards,” said Donna Bohanon, chair of the Black History Committee. “They’re not segregated in one area, but throughout Loudoun County.”

Some of the county’s recent developments are located in and around what used to be historically Black neighborhoods. In the middle of South Riding is Prosperity Baptist Church, and the relocated Settle-Dean Cabin, which existed when the area was known as Conklin.

Other African American villages remain intact. St. Louis, which is located six miles west of Middleburg, dates from 1891 or earlier.

“There are property owners in St. Louis who have owned land and lived there for generations,” said Heidi Siebentritt, who is the principal planner for historic preservation in the Loudoun County Department of Planning and Zoning.

Recognized as the heart of Virginia’s horse and hunt country, Middleburg’s history has been well-documented — not so, for the many African Americans who worked in Middleburg and lived in St. Louis.

“A lot of the people were working in the equestrian industry in Middleburg, as groomsmen, as jockeys — and they were experts, very skilled at it,” said Bohanon.

“African Americans were able to purchase land — it wasn’t necessarily the best land in the area — still, they were able to purchase land to build homes and a church,” said Bohanon. “Later, the community of African Americans petitioned to get a school built … Banneker Elementary School.”

Banneker opened in 1948 and is still open.

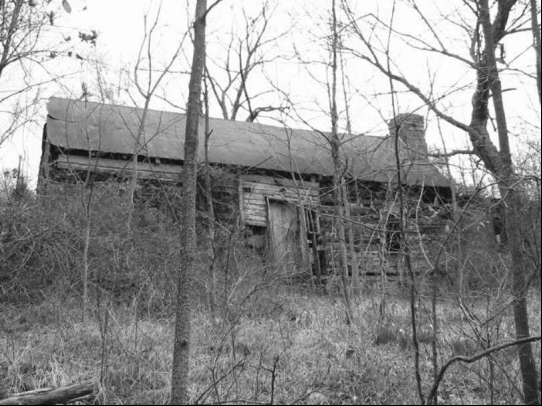

Loudoun County has contracted with surveyors, who are photographing and documenting architectural, archaeological and landscape elements in St. Louis, and other historically Black communities.

The county has a far-less-complete history of African American towns, villages, and neighborhoods — which can pose a problem for future development.

“If we don’t have the information on these resources, we don’t have a way to bring them to the forefront as part of the land use and development process,” said Siebentritt. Knowing the history will provide the county with the knowledge “to request, or even require some sort of preservation or mitigation.”

Siebenbritt said gaining the history now is important. “There’s development pressure, and these neighborhoods are changing, not unlike a lot of places in western Loudoun County where residential development is a pressure,” he said.

In addition to the structures, Bohanon’s research includes trying to learn more about the people who lived — or still live — in the historically African American towns, including social organizations “that were established to uplift the community’s safety and well-being during enslavement, Jim Crow, and all other repressive times,” Bohanon said. “We can ask those questions of the descendants of the community who may know the answers.”