@PrinceGeorgesMD joins world in mourning loss of #RIPMuhammadAli. He was Greatest Of All Time at being a humanitarian, not just at boxing.

— Rushern L. Baker III (@CountyExecBaker) June 4, 2016

"Service to others is the rent you pay for your room here on earth." #RIPMuhammadAli pic.twitter.com/8rKB9WoiTN

— MurielBowser (@MurielBowser) June 4, 2016

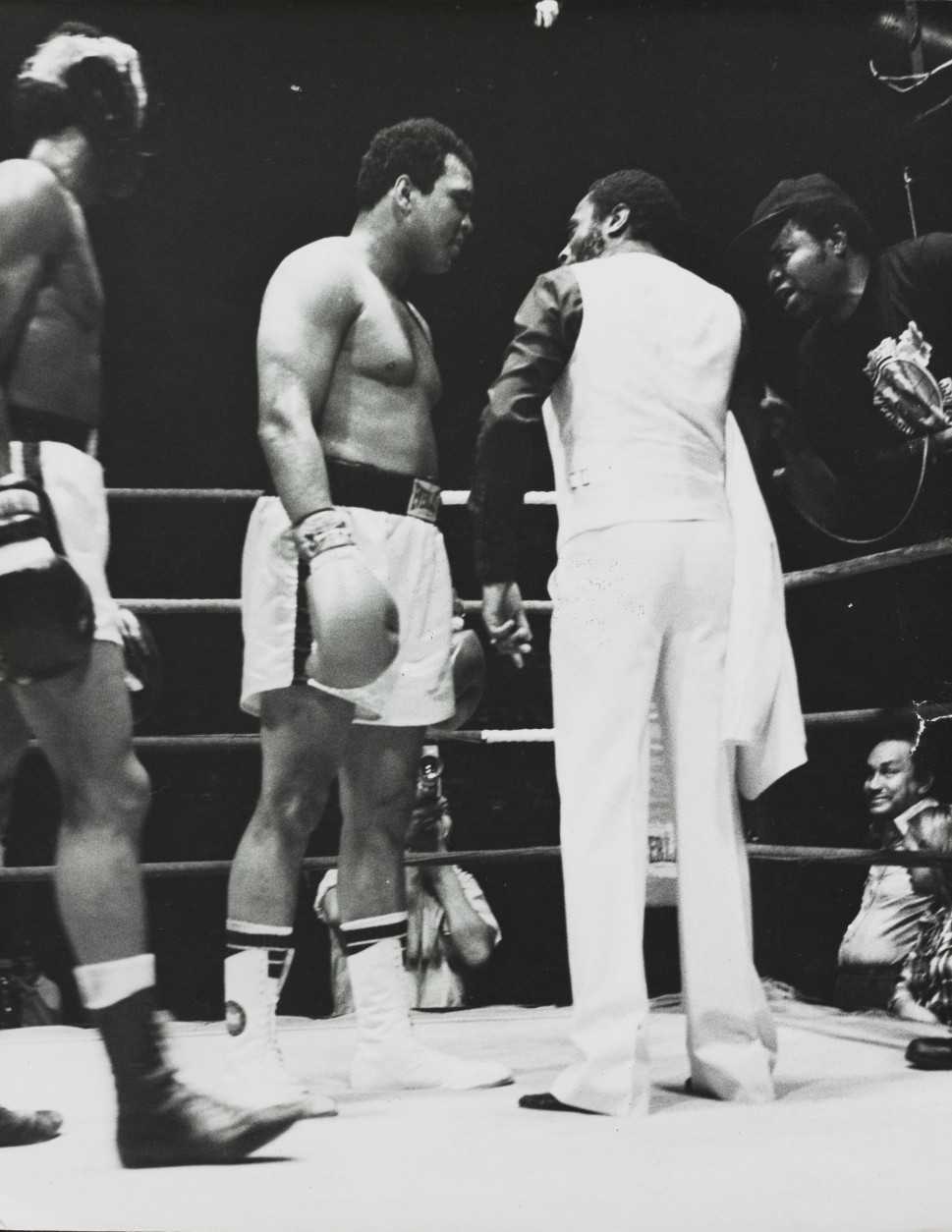

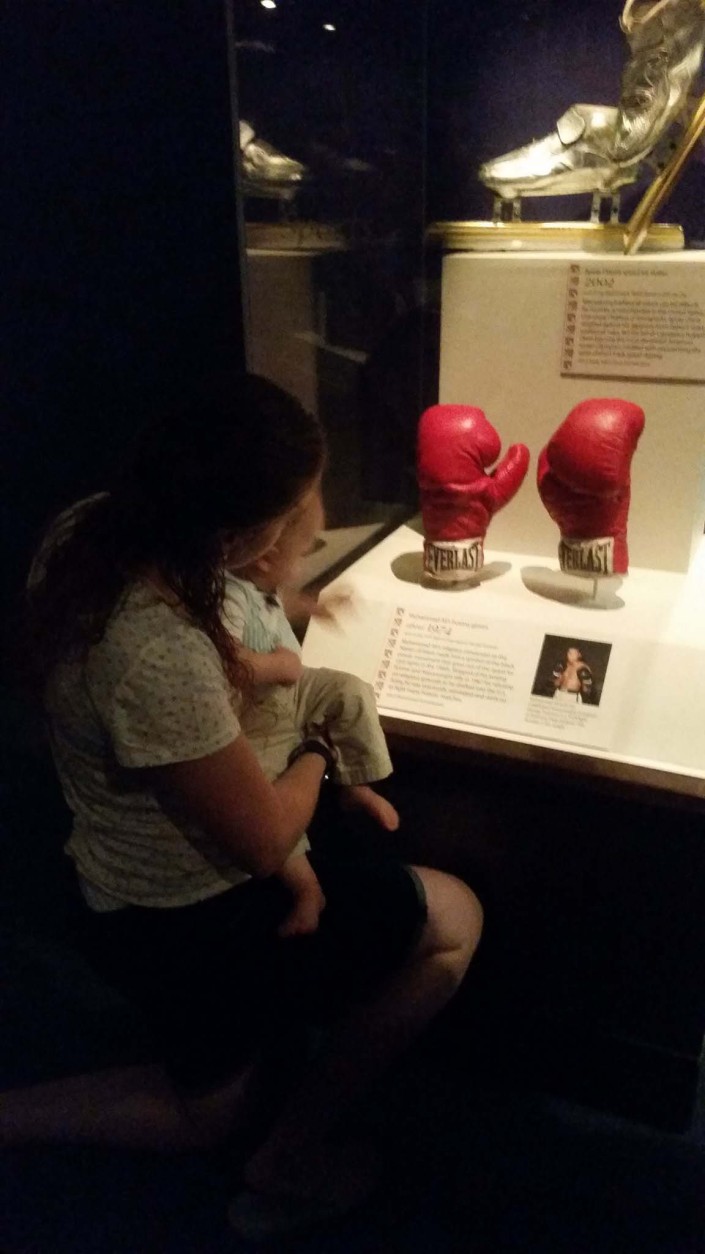

WASHINGTON — On Saturday, people stood in front of the glass case with the bright red boxing gloves inside, taking pictures, and sharing their memories of a man who was an icon to many.

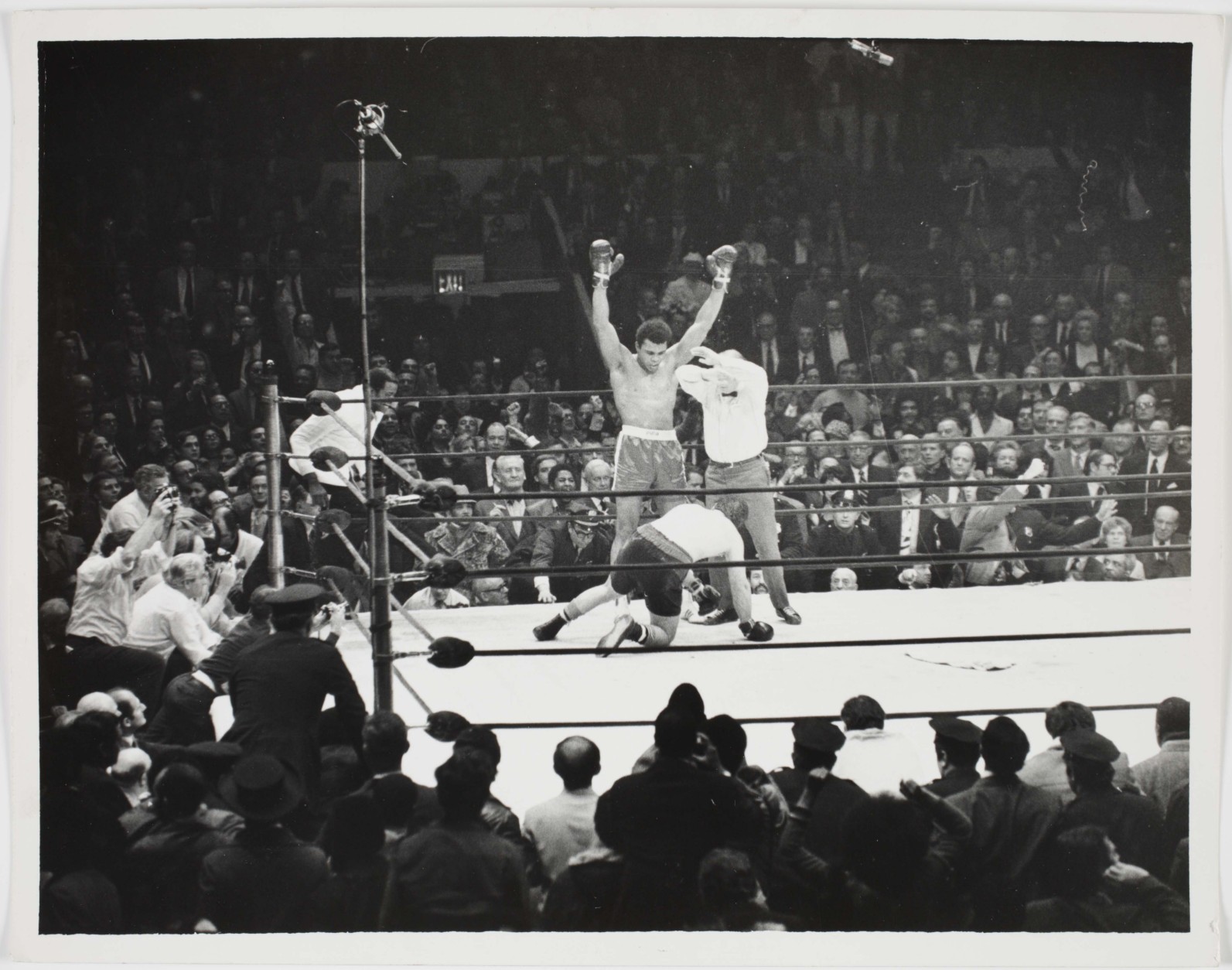

“He was great in the ring and out of the ring too … and a very respected man,” said Tracy Fox, who was visiting the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History from Connecticut. “He was the greatest boxer ever, and champion, and ‘float like a butterfly sting like a bee’!”

The museum has the boxer’s Everlast gloves. Mark and Marie Farrell stood in front of the display, and talked about the man they both admired.

“Muhammad Ali, the greatest that ever lived,” laughed Marie Farrell. “I was probably maybe 8 at the time.”

“I remember all of his quotes and his bantering with (sportscaster) Howard Cosell,” said Mark Farrell.

Though she came to pay respect to the gloves, Jessica Rucker of D.C. said she thinking about Ali’s battles for justice.

“I think he was an incredibly complex and nuanced man who was not only a heavyweight champion, but a champion for black liberation, and for human rights, both in the United States and abroad,” Rucker said. “I appreciated how he used his platform as an athlete to raise awareness for civil and human rights.”

Lonnie Bunch, founding director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, said Ali used both his visibility as a fighter, and visits to college campuses, to support the civil rights movement.

“But more importantly, he demanded that there be a sense of black pride,” Bunch said. “He made people feel that black people were as good as anybody on this earth, and therefore he inspired generations to care.”

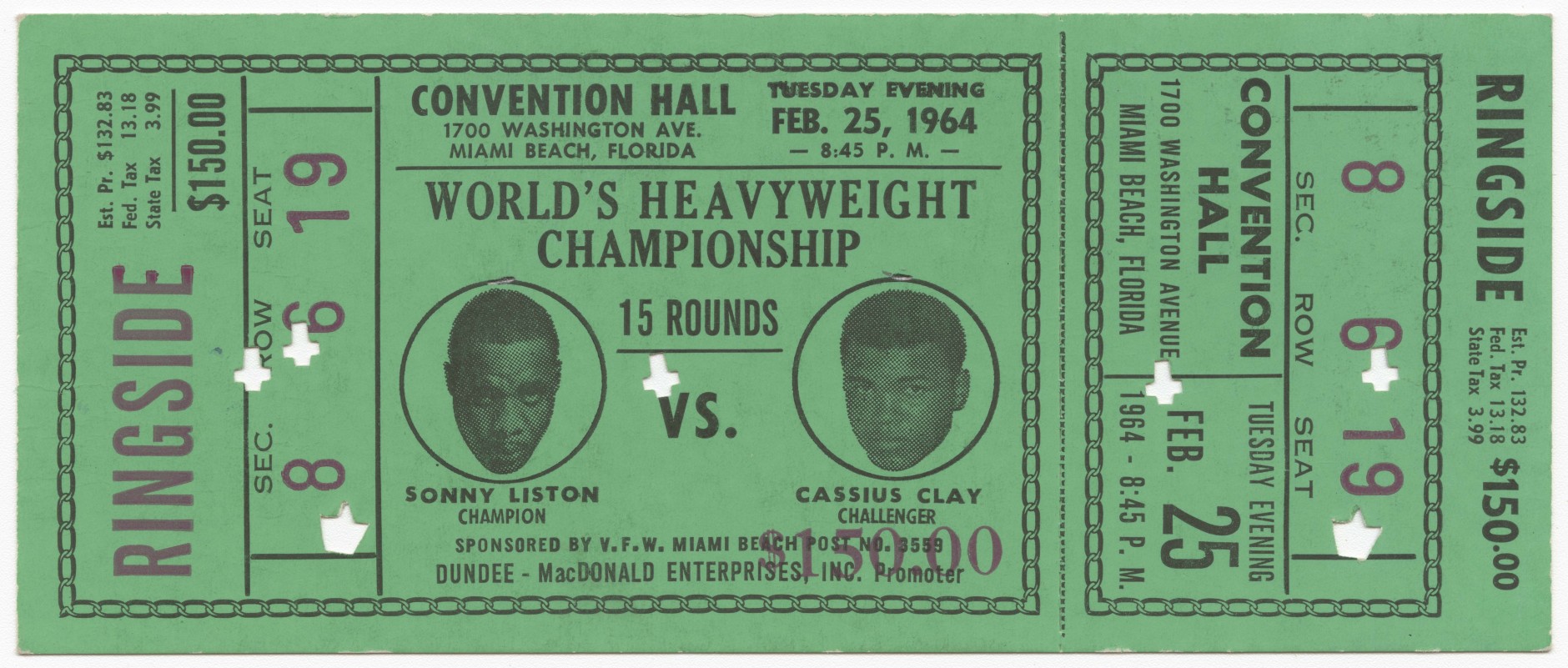

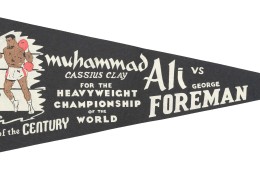

Bunch said Ali was a symbol of what many African Americans thought would be a new day for black people, even though he stunned the nation when he joined the Nation of Islam.

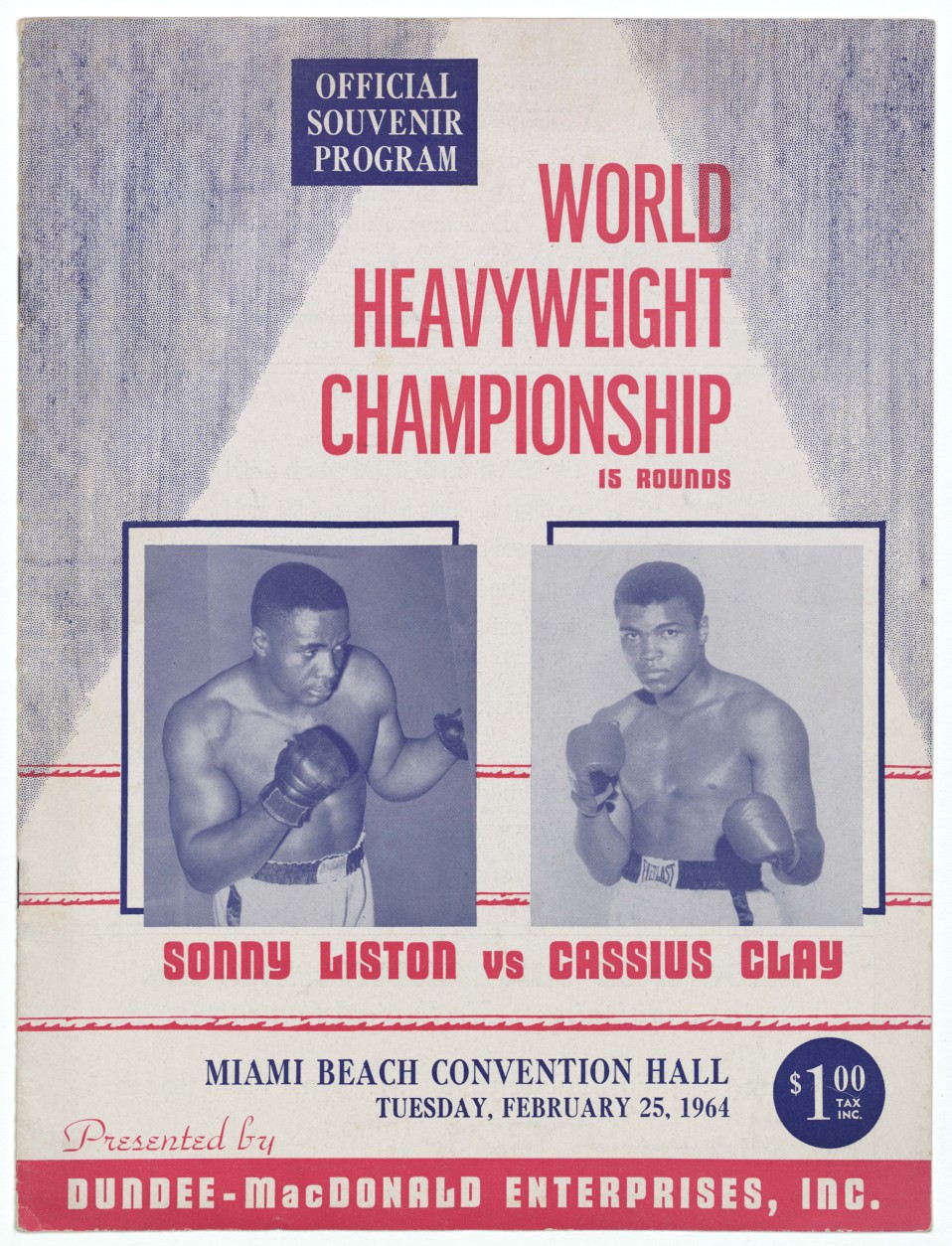

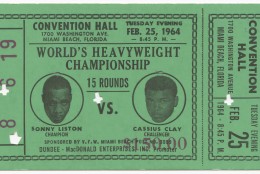

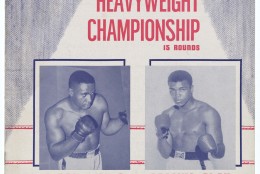

“The Nation of Islanm in 1964 was seen as this radical militant group that was unknown to many Americans, black and white,” Bunch said. “In some ways, he became a symbol of what some people perceived as the militant new Negro. … So Ali carried the burden of not only having to be a good fighter, but he carried the expectations, especially of a younger generation, of what being black in America could mean.”

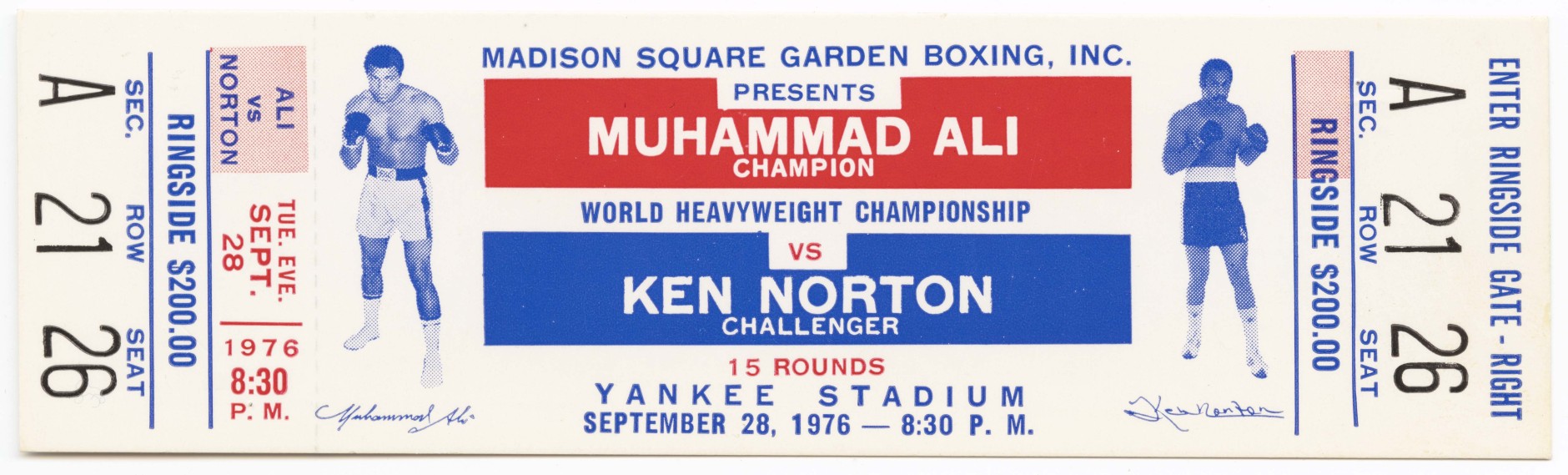

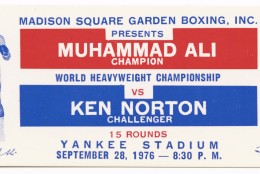

Bunch said that Ali was a man who believed in his religious convictions, and his career suffered from that.

“It was more important for him to be a man of God, to be a man of the Nation of Islam, than to go to Vietnam and his career suffered from that,” Bunch said.

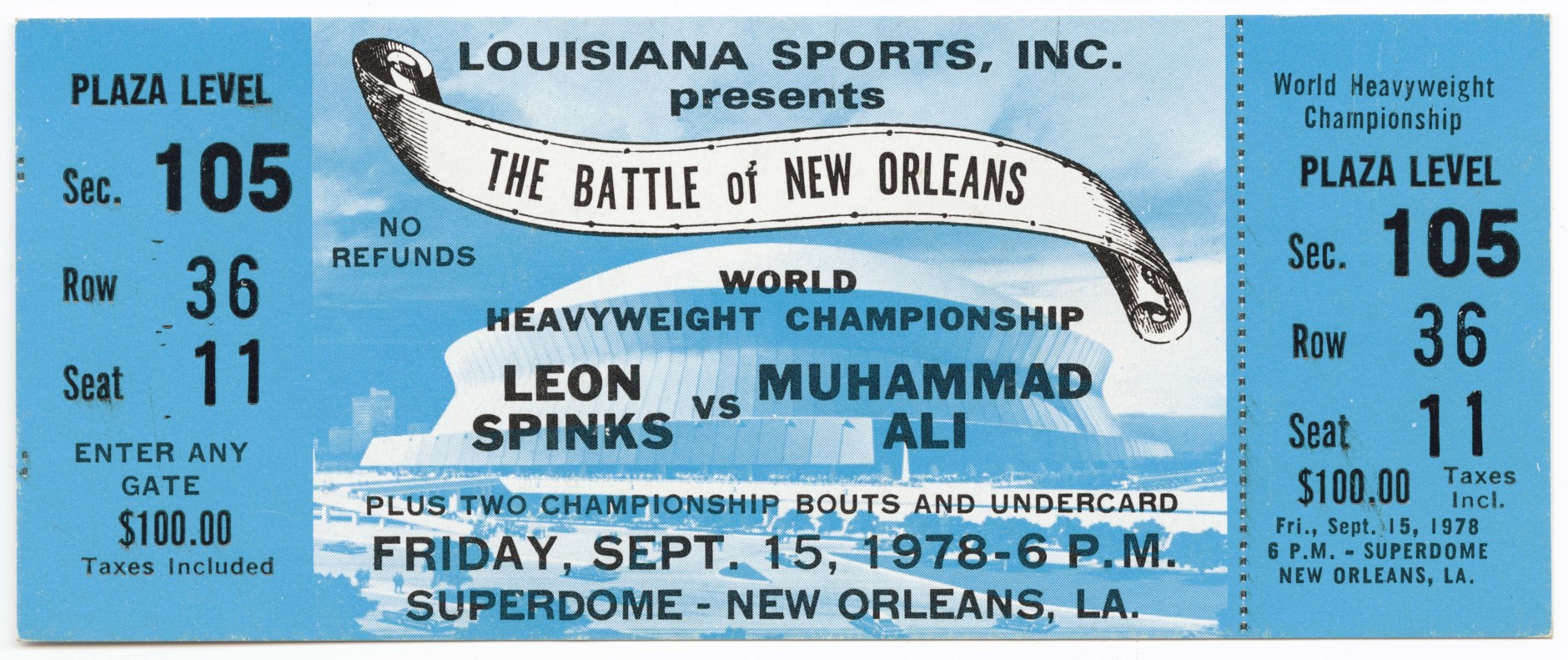

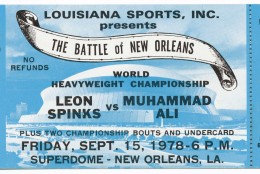

But in his later years, Bunch thinks Ali’s greatest achievement is the visibility he turned on to Parkinson’s disease, even though the horrible illness stripped him of many of the things he did best, from his movement to his verbal dexterity.

“You could still see in his eyes, and his spirit, that nothing could kill the spirit of Ali,” Bunch said.

WTOP’s Lara Bonner contributed to this report.