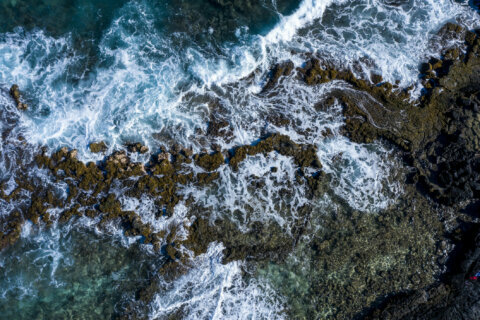

Summer is here and millions of people are flocking to beaches all across the country. But even on a seemingly beautiful weather day, a hidden danger can lie just under the surface: rip currents, high surf or sneaker waves — collectively known as surf zone incidents.

Not all of these occur in the ocean. Dozens of people die each year at American lakes.

A rip current is defined by the National Weather Service as “a relatively small-scale surf-zone current moving away from the beach. Rip currents form as waves disperse along the beach causing water to become trapped between the beach and a sandbar or other underwater feature. The water converges into a narrow, river-like channel moving away from the shore at high speed.”

High surf refers to large waves breaking on or near the shore due to swells spawned by a distant storm. And sneaker waves are simply big waves that suddenly swamp a beach and often take people by surprise, sweeping them into the water.

Together, these surf zone incidents account for over 100 deaths on average annually. That is more than the average annual deaths from hurricanes, lightning or tornadoes.

“On days with high surf and potential for dangerous currents, a simple rule the National Weather Service stresses is to ‘stay dry when waves are high’,” says Matt Friedlein, lead forecaster with the National Weather Service in Chicago.

Rip currents alone account for an average of 60 deaths annually. That rose to 66 in 2020, and is already at 49 so far this year, ahead of pace.

There’s some recent good news for beachgoers on that front: Forecasters now have a model that can predict the probability of rip currents up to six days out.

Still, some states and Puerto Rico are ahead of pace regarding surf zone-related fatalities compared to previous years. Florida has 21, an increase from 16 in all of 2020. Texas, California and Puerto Rico have higher numbers than they had in all of 2020. Rhode Island, Oregon and Wisconsin are currently tied with their 2020 total numbers

Wisconsin? Yes, you read that correctly. Just because Wisconsin does not sit along the ocean does not mean residents are risk-free.

Surf zone risks not limited to oceans

There is a common misconception that surf zone-related deaths only occur near oceans. In 2020, there were 28 fatalities along the Great Lakes, meaning nearly one third of the annual surf zone fatalities in 2020 were from the Great Lakes region.

“Great Lakes waves tend to arrive at shore in closer succession than ocean waves, which can make it harder for a swimmer to recover if they are knocked down,” says Friedlein. “The shorelines also have many piers and break walls where strong currents can develop and surround, as well as gaps in sandbars that favor currents.”

Each summer, there are an average of 12 fatalities and 23 rescues on the Great Lakes due to dangerous currents, according to the National Weather Service’s Great Lakes swim season summary database.

“In general, the weather conditions most favorable for rip currents are onshore directed strong winds of 15+ mph sustained speed, and waves greater than 3 feet,” Friedlein explains. “Lake Michigan in particular has a long north-to-south orientation, which with stout northerly or northwesterly winds behind cold fronts can result in water piling up significantly along the Indiana and Michigan shores, creating favorable conditions for high surf and strong currents.”

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), rip currents typically reach speeds of 1 to 2 feet per second. However, some rip currents have been measured at 8 feet per second — faster than any Olympic swimmer ever recorded. So even if you are an excellent swimmer, you may be no match for a swift moving rip current.

“Typically, with rip currents people get caught off-guard,” says CNN meteorologist Rob Shackelford. “They find themselves being pulled away from shore quickly, panic sets in and they find they don’t know what to do to get back to shore safely.”

Friedlein says the key is to stay calm.

“Do not try to swim directly back to shore, as this will only cause fatigue and worsen the situation,” Friedlein cautions. “Instead, a swimmer will want to swim to the side, or parallel to shore, to exit the channel of stronger flow that can often form in a gap in a sandbar. Once out of the current and not being pulled away from shore, the swimmer then should swim back to shore.”

There often are visual signs of a rip current that you can look out for. For example, the rip current may appear darker than the surrounding water. Usually, you can look for areas where waves do not break, flanked by areas where the water is breaking. Knowing some of these warning signs can be lifesaving.

NOAA launches new forecast tool

NOAA has recently launched a national rip current forecast model in an effort to broaden awareness and implement life-saving alerts.

This new tool can predict the hourly probability of rip currents along US beaches up to six days out, allowing critical information to get out in a timely manner.

“Safety for beach-goers and boaters is taking a major leap forward with the launch of this new NOAA model,” said Nicole LeBoeuf, acting director of NOAA’s National Ocean Service, in a statement.

“Extending forecasting capabilities for dangerous rip currents out to six days provides forecasters and local authorities greater time to inform residents about the presence of this deadly beach hazard, thereby saving lives and protecting communities.”

If you find yourself headed to the beach, don’t just check the forecast to see if it will rain, but also if there is a threat for dangerous surf zone conditions.