ARLINGTON, Va. — As the #MeToo movement sweeps across the country, some survivors of military sexual trauma are asking: What about them?

“Where is the ground swell for support for us,” said Lydia Watts with Service Women’s Action Network. She said they are looking for the #MeTooMilitary reckoning.

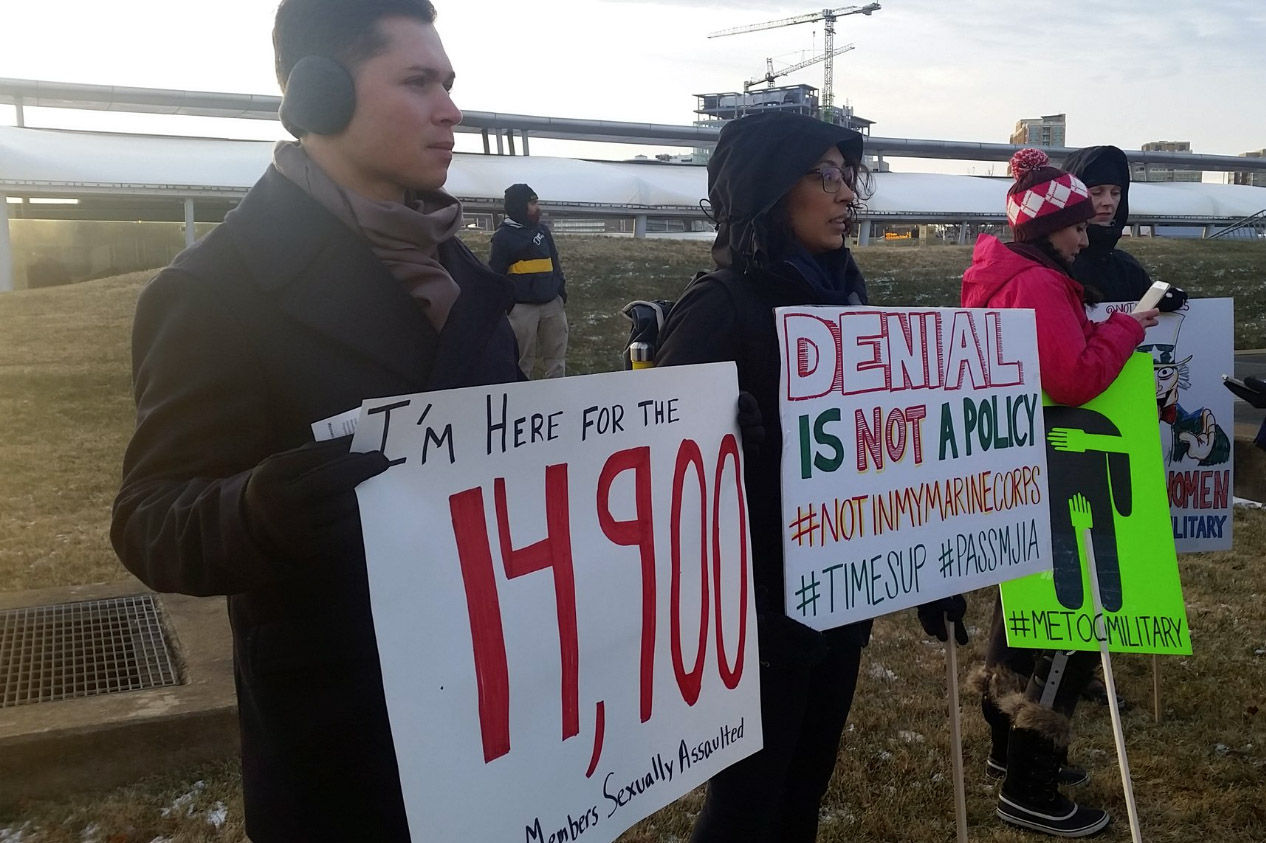

Watts spoke to a crowd of about 40 demonstrators in the frigid cold outside the Pentagon on Monday morning to raise awareness about the epidemic of military sexual harassment and assault.

“We know that it’s a big problem. We know that 6,300 reports of sexual assault were made in 2016,” Watts said.

An estimated one in three cases is ever reported, she said.

The Pentagon acknowledges the problem and said steps are being taken to address it.

Some in the crowd who were survivors of military sexual trauma and shared their stories.

Nichole Bowen Crofton traveled from Washington state to speak out on Monday. She is an Army vet who served in Iraq.

“I’m scared to tell my story. But standing up for the men and women who serve our country who can’t report sexual assault in a safe way is more important than my feelings,” Bowen Croften said.

She said she was sexually assaulted in 2003 by a high ranking sergeant. But her supervisors, whom she trusted, suggested she not report the assault out of concern for her career and the chance of retaliation.

According to the Pentagon’s 2016 Annual Report on Sexual Assault in the Military, about 58 percent of service members who reported that they were sexually assaulted faced retaliation.

Watts said the Pentagon is aware of the sexual assault problem.

“But what we want is action around that 58 percent of those who reported faced retaliation for reporting. Their careers are the ones being impacted, not their assailants.”

She said that, of the cases that are brought forward, there is only a 4 percent conviction rate.

Don Christensen, president of Protect our Defenders, said retaliation often results in women being forced out of the military. But about half of all sex assault survivors in the military are men.

Christensen said the Pentagon knows there’s a problem. He said they want military leaders to quit obstructing reform and actually work with members of Congress in the Senate and House who want to reform the system.

He said one of the problems with military justice is that it is controlled by commanders, and the commanders are often going to have a bias in the process.

They often know the accused. They usually value the accused, than they do the victim. And so what we’re looking for is to reform the process. Make it a professional military justice process where prosecutors make decisions instead of commanders.”