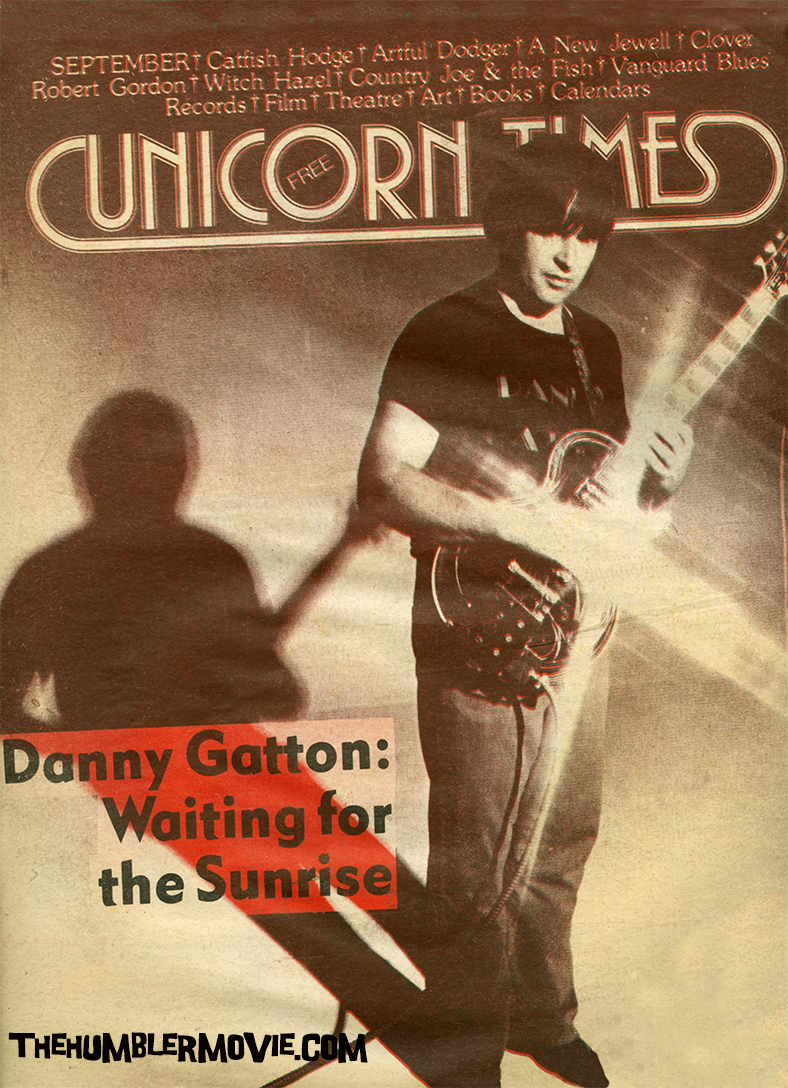

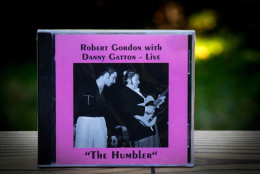

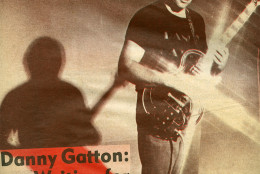

WASHINGTON — Danny Gatton, the D.C.-based musician whose virtuosity and reluctance to embrace stardom earned him the title “the greatest guitar player you’ve never heard,” is the focus of a currently-in-production documentary, “The Humbler: Danny Gatton.”

The film’s director, Virgnia Quesada, said Gatton’s distinctive style was legendary and wide-ranging.

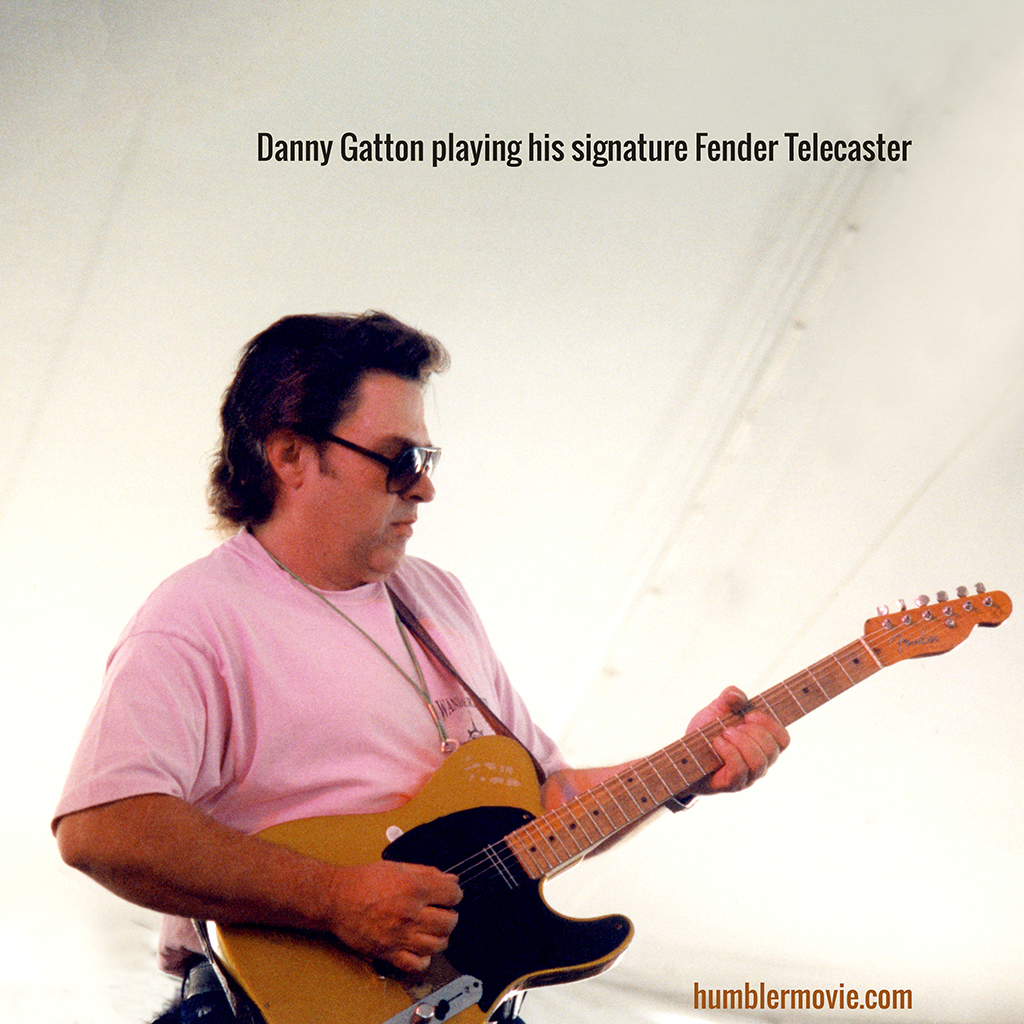

“He could tell the history of guitar in one song,” said Quesada. “He fused together blues, jazz, rockabilly and country.”

Gatton was born in the Anacostia section of Washington, D.C. in 1945. He committed suicide in 1994, at the age of 49.

“He started playing when he was nine, and by 14 he was playing out in clubs,” said Quesada. “He was like a sponge — if he heard it, he could play it authentically.”

Fellow musicians bestowed Gatton with a nickname: The Humbler.

Unable to read music, Gatton developed a right hand picking technique, combining a flat pick and using his fingers for speed — “that came from his early banjo days,” Quesada said.

Blessed with perfect time and relative pitch, Quesada said several factors likely contributed to Gatton’s guitar supremacy and his aversion to aspects of the music industry that could have made him more money.

On Thursday, Quesada, and her nonprofit organization Video Culture, Inc. launch an Indiegogo crowdfunding effort, to raise $36,000 for help complete the film, which she began working on in 1989, while Gatton was still alive.

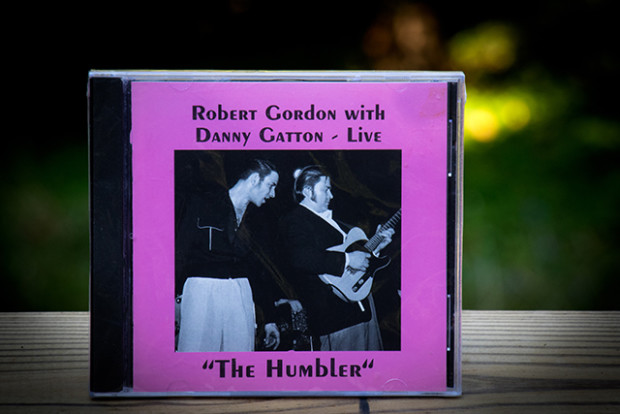

Gatton was a staple on local stages in the 1970s and 1980s, as a solo performer and with Redneck Jazz Explosion, with pedal steel legend Buddy Emmons.

In 1991, Gatton signed a multi-album major label record deal with Elektra, after several releases on small labels, including one owned by his mother, Norma.

Entertainment attorney John Simson, a board member of Video Culture, was Gatton’s manager in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

He remembers the first time he saw Gatton perform.

“My mouth dropped — I couldn’t believe what I was watching,” Simson said. “You’d think there were two or three people playing at once.”

Simson and Quesada said Gatton’s unwillingness to tour limited his options.

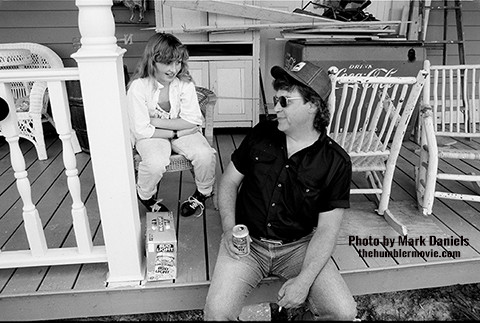

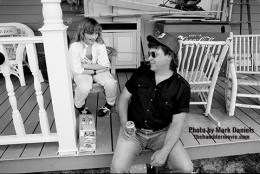

“He was a family man, who liked to be home and work on his car and be with his family,” said Quesada.

However, Gatton’s foibles likely hampered his rise to stardom beyond the awe of fellow guitarists, including James Burton, Albert Lee, Steve Vai, Slash and Richie Sambora.

“He was painfully shy,” Quesada said. “I heard from his mother and wife he would be happier if he could have played behind a curtain where you couldn’t see him and he didn’t have to engage.”

Soon after Simson began his management duties, musician magazines started heralding Gatton’s abilities, yet he continued to avoid life on the road.

“Certainly Danny was a reluctant professional musician,” Simson said. “Don’t get me wrong, he loved playing, but he also liked working on his cars, and frankly, he was kind of marching to his own beat.”

At the time, touring was an important part of an upcoming musician’s career.

“It’s hard to get known, especially in that era when you don’t have the internet,” said Quesada. “You have be a physical presence — you have to do that road time.”

In the 1990s, the heyday of CDs, Simson said a performer who sold a lot of albums could more easily avoid constant touring.

However, Simson said Gatton’s music was difficult to pigeonhole, which made it difficult to get radio airplay.

“For an instrumental artist who’s not writing lyrics and not writing songs that are likely to blow up on radio, when was the last time you heard an instrumental on Top 40 radio,” asked Simson, who cited “Dueling Banjos” from Deliverance in 1972 as an exception in his lifetime.

Quesada said Gatton’s desire to stay near home trumped the benefits — and demands — of becoming a household name.

“I think he missed the money, but he didn’t really want to make it, ” said Quesada. “His mother used to say he’s like Teflon — success slides off him.”

After years of speaking with the people closest to Gatton, including his wife, mother, and bandmates, Quesada said it appears Gatton was unwilling to take the risks associated with superstardom.

“I don’t know if it’s entirely true, but I think there was a fear of success,” Quesada said.

Her research and interviews leads her to believe physical ailments may have played a role in Gatton’s suicide.

“Danny was having some strokes, which was sort of a paralysis on the left side of his body where he couldn’t feel anything, and I think that scared him a lot,” Quesada said.

Longtime bandmates and family members had some hints of Gatton’s depression.

“I think today he might be diagnosed as bipolar, because he had those big swings where he’d be really up and happy go-lucky,” said Quesada. “And when he was in his sadder state, he just hid, and people didn’t see it.”

The strokes took their toll on Gatton, according to those who spoke with Quesada.

“It’s conceivable that he was afraid of being a burden on folks, and that he’d become really handicapped by the strokes he was having,” said Quesada. “He took his life on Oct. 4, 1994, in his garage.”

Making ‘The Humbler: Danny Gatton”

Quesada said the documentary doesn’t dwell on Gatton’s untimely death, but celebrates his music, and the effect it had on musicians and the public.

“I always felt I wanted the film to be a healing piece to help us recover from the loss of this great artist and his music,” Quesada said.

Gatton was involved in the early stages of the movie, with performances and interviews.

Others who have already been interviewed include Les Paul, Vince Gill, Gatton’s late mother, wife and daughter.

“At this point we’re almost done with principal photography, we’re going into editing,” said Quesada, on the launch of the Indiegogo crowdfunding effort.

Quesada hopes to do more interviews with celebrities who have voiced admiration for Gatton.

In addition, the money raised will go toward the first edit of the film, said Quesada.

She acknowledges eventually more money will need to be raised to pay for music licensing, “which has gotten a little more elaborate than it had been, back when,” said Quesada. “Then some sweetening — that’s about it.”

A lot of the video footage was originally shot in standard definition, “but the product will be high-def,” said Quesada.

Many younger fans have learned about Gatton online.

“YouTube has kept Danny alive, and not only alive, but probably blossoming,” she said.

Quesada said the finished film will be 90 to 100 minutes, and hopes it will be completed by July 2017.

After almost 27 years in the making, “I’m seeing the light at the end of the tunnel,” Quesada.

Here’s the first look at the trailer for “The Humbler: Danny Gatton.”