WASHINGTON — There’s no word yet on why information on stop-and-frisk encounters hasn’t been compiled and made public by D.C. police, but a Superior Court judge wants to hear the plan for how it’s going to happen.

A provision of the Neighborhood Engagement Achieves Results, or NEAR, Act of 2016 passed by the city council requires D.C. police to collect comprehensive data on all stops and frisks conducted in the District beginning in October 2016. That hasn’t happened.

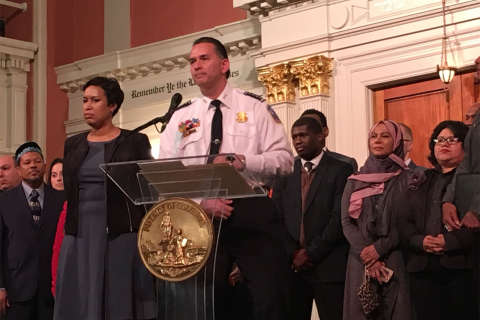

So, Black Lives Matter D.C., Stop Police Terror Project D.C., and the American Civil Liberties Union of the District of Columbia has sued, asking for a court to order D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser, the police chief and other top D.C. officials to comply with the NEAR Act requirement.

In court Friday, the judge said he wants the parties to get together to confer and see him again next week to propose a schedule for government disclosures and/or start interim measures to comply with the NEAR Act.

“He made it clear he was going to order the District to take action, whether that be to provide information or to provide interim action of some kind within the following two to four weeks,” said Scott Michelman of the American Civil Liberties Union of D.C.

“This is more movement than we’ve seen from the District in the first 2-and-a-half years of this law’s existence. So, that’s a good thing,” Michelman said.

The ACLU and other groups want stop-and-frisk information detailing who was stopped, why and what happened.

“We have heard many reports of police encounters with, in particular, African-American men that suggest that police have a problem dealing with that community,” Michelman said. “(Reports) that they are presumptively treating black folks as suspects and behaving disrespectfully toward them.”

Michelman said the data can show whether the department is overpolicing. “Or, if, as the police claim, there are just a few bad apples and isolated incidents,” Michelman said.

D.C. police responded to WTOP’s request for comment, saying that they declined to comment on pending litigation.

The city’s response to the lawsuit in court documents from June 2018 state that none of the plaintiffs has shown they’re injured by the alleged “unreasonable delay” and that the groups have no standing to act on behalf of people who might be aggrieved.

The response, according to the documents: “Plaintiffs fail to explain why their members cannot pursue constitutional claims on their own if they are, in fact, being unconstitutionally targeted by MPD officers.”