WASHINGTON — It’s been called the ultimate party song, so it’s hard to imagine it was once the subject of an FBI investigation.

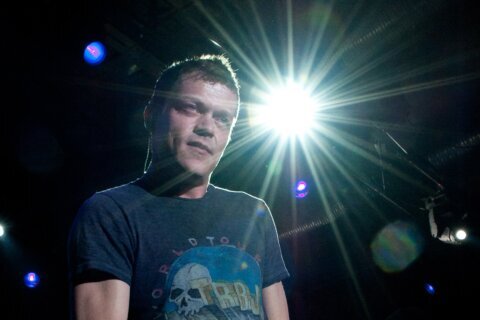

Jack Ely, who died Tuesday at the age of 71, got “quite a kick” out of the FBI’s two-year, 455-page obscenity investigation into The Kingsmen’s “Louie Louie,” says his son, Sean.

The song, which held the No. 2 spot on the Billboard charts for six weeks in 1963, was initially intended as an instrumental, but at the last minute his father decided to sing it, Sean says.

The low-budget hit is known for both its simple chord progression and largely unintelligible lyrics.

According to Sean Ely, the recording engineer had set up a single microphone high above his father’s head, forcing him to stand on tiptoes and shout to be heard.

At the time, the Federal Bureau of Investigation didn’t know that.

According to FBI documents, a concerned father in Sarasota, Florida’s note to then-Attorney General Robert Kennedy spurred the FBI’s probe into whether the song violated the Federal Interstate Transportation of Obscene Matter statutes.

Here’s the timeline of the government’s investigation into “Louie Louie.”

January 30, 1964: The father of the high school student, whose name was excised in the FBI file, wrote Kennedy in a letter: “Who do you turn to when your teen age daughter buys and brings home pornographic or obscene materials being sold along with objects directed and aimed at the ‘teen age market’ in every City, Village, and Record shop in this Nation?”

This father, and others across the country, according to FBI documents, had discovered their children had handwritten or typed copies of lyrics, supposedly of The Kingsmen’s “Louie Louie.”

“The lyrics are so filthy that I can-not enclose them in this letter,” the father wrote. “When they start sneaking in this material in the guise of the latest ‘teen age rock & roll hit record, these morons have gone too far.”

February 7, 1964: The letter became part of an FBI criminal investigation, according to date stamps on the document.

Simultaneously, other agencies were investigating the quickly-rising hit record.

February 13, 1964: The Federal Communications Commission, in a letter to The Kingsmen’s label, Wand Records, wondered if “there was improper motivation on the part of the singers or anyone associated with the production of the record in making the recorded lyrics so unintelligible as to give rise to reports that they were obscene.”

February 14, 1964: Wand Records wrote the FCC: “All the people connected with the making and then sales of this record are highly reputable business people who are as vitally concerned with this matter as you are and wish to bring to justice anyone connected with the dissemination of libelous information.”

The label owner told the FBI “to the best of her knowledge, the trouble was started by an unidentified college student who made up a series of obscene verses for this recording and sold them to fellow students.”

The label owner also offered access to the two-track recording, so the FCC could isolate the vocal track.

The National Association of Broadcasters had also received copies of the lyrics, and told the FBI: “The lines, delivered in rock and roll and Calypso style, would be unintelligible to the average listener.”

Yet, armed with the lyrics being circulated, “The phonetic qualities of the recording are such that a listener possessing the ‘phony’ lyrics could imagine them to be genuine,” the NAB concluded.

March 16, 1964: The FBI file included a notation that a record owner “had heard from various acquaintances the record had obscene lyrics on the “LOUIE LOUIE” side, when played at a speed of 33 1/3 instead of the normal 45 rpm.”

March 23, 1964: In an entry labeled “Obscene” in capital letters, underlined twice, the Bureau file includes lyrics, that include the F-word, as well as hell, bitch, lovemaker, bone, and lay.

March 24, 1964: Indianapolis-area federal prosecutor Lester Irvin said if the FBI determined the lyrics to be obscene, he would consider prosecuting the case.

March 27, 1964: A copy of The Kingsmen record and a typewritten sheet of the allegedly obscene lyrics were forwarded to the FBI lab.

April 17, 1964: FBI headquarters forwarded the lab’s results to its Indianapolis field office in a memo.

“For your information, the record was played at various speeds but none of the speeds assisted in determining the words of the song on the record,” wrote FBI HQ. “Because the lyrics of the song on the record could not be definitely determined in the Laboratory examination, it could not be determined whether (Louie Louie) is an obscene record.”

May 13, 1964: The lack of confirmation from the FBI lab was enough for Irvin to reconsider his willingness to prosecute.

According to a memo, Irvin “advised he would decline prosecution in this case since the FBI Laboratory is unable to determine this record is obscene.”

May 15, 1964: An entry in the file states “no further investigation is to be conducted in this matter.” In a handwritten jotting on the memo, it’s noted the FBI’s 45 rpm copy of “Louie Louie” was disposed of by the lab.

June 18, 1965: More than a year after the FBI declared the probe dead, it was revived when a mother and teacher wrote directly to FBI director J. Edgar Hoover. She wrote that with conflicting versions of “Louie Louie” lyrics, “Without a doubt, someone has masterminded an ‘auditory illusion,'” the unidentified woman wrote.

“Mr. Hoover, do you think more of these type records are inevitable,” she wondered. “Is there perhaps a subliminal type of perversion involved?”

June 25, 1964: In his response, Hoover said while he couldn’t comment about the ongoing investigation, “I strongly believe that the easy accessibility of such material cannot help but divert the minds of young people into unhealthy channels and negate the wholesome training they have already been afforded by their parents.”

August 23, 1965: In a letter, the FBI special agent in charge in New York informed Hoover the label owner “had been mistaken when she had previously advised that the record ‘Louie Louie’ had been made from a two track recording,” when it was actually recorded in mono. “There is no separate voice track recording for the record “Louie Louie.”

September 21, 1965: The FBI spoke with Richard Berry, who wrote and originally recorded “Louie Louie,” in 1956. The song had been covered in 1961 by the Wailers, and became a local hit in Seattle.

According to an FBI memo, Berry “stated that possibly the rumor that the record was obscene contributed to its sales record; however he pointed out that if this were true, it was entirely unintentional.”

September 1965: The Bureau interviewed several members of The Kingsmen, who were informed they could consult with attorneys.

Each of the members, whose names were not revealed in the FBI online file, said with a short rehearsal session, there was “certainly no deliberate attempt to include any obscene or suggested (sic) wording.”

In fact, one band member told the agent the record company, Wand Coporation “offered a $1000 reward to anyone who could substantiate the reported obscenity.”

According to one band member: “Those who want to hear such things can read it into the vocal.”

Some had suggested The Kingsmen rerecorded the song, to include hard-to-hear obscenity, but band members told the FBI the vocals were only recorded once.

October 29, 1965: An FBI memo notes “Members of ‘The Kingsmen,’ who recorded the controversial version of ‘Louie Louie,’ upon interview reported it definitely contained no obscenity.”

December 12, 1965: With the probe sputtering, a Detroit prosecutor, Robert Grace, concluded there was “no evidence of a violation of the Federal Interstate Transportation of Obscene Matter statutes.”

After almost two years of the probe, Grace recommended “that no further investigation in this matter be conducted.”

See the complete FBI file here:

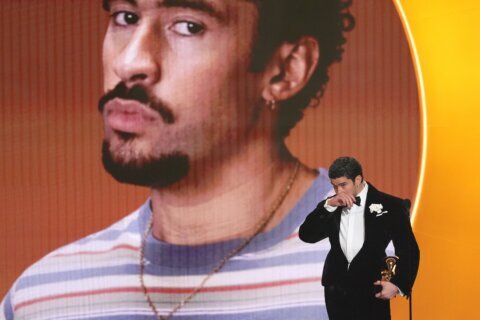

Listen to “Louie Louie” as recorded by The Kingsmen.