WTOP’s Thomas Warren’s week-long series “Generation Positive” is an in-depth look at the HIV epidemic in the U.S. and Washington, D.C. In a four-part web series and an eight-part series on-air, he will be taking a look at measures being taken to beat HIV/AIDS and breakthrough developments in the search for a vaccine.

Thomas Warren, wtop.com

WASHINGTON – On New Year’s Eve 1986, Patricia Nalls was a married mother of three.

The next day, as the year changed, so would the direction of her life.

Her husband, Lenny, was a veteran of the Air Force, and worked as an aeronautical engineer. They met when she was 19, and he quickly became the love of her life.

Lenny also had been an intravenous drug user while in the service, but had reached 10 years of being clean.

Lenny contracted AIDS from his days using drugs. It’s also how Patricia got the virus when she was 29.

On New Year’s Day 1987, two months after being diagnosed, Lenny died.

The 1980s were still a time when so little was known about HIV/AIDS.

Patricia said because Lenny had not done drugs in 10 years, he was not thought to be at risk.

“We bought a home. Our children were in private school. Everything was going fine,” Patricia said. “Unfortunately, people didn’t think to ask those questions, because we were whatever they thought we were.”

Patricia became a single mother of 8-year-old Nikki, 4-year-old Shawn and 3-year-old Tiffany.

Miraculously, Nikki and Shawn were born HIV-negative.

Patricia says Tiffany was very sick when she was born, but no one knew what was wrong with her.

“She spent practically most of her time in the hospital,” says Patricia, who is from Virginia.

Tiffany had AIDS.

She died six months after her father.

Because of a low T-cell count at the time she was diagnosed, Patricia was told she had a short time left before she would follow Tiffany, and Lenny.

“I was 80 pounds. I was given less than two to live. It was horrible,” she said. Her days consisted of taking her two kids to school, then spending the rest of the day violently ill.

Pat Nalls talks about the early years of being HIV-positive

She was on disability, and couldn’t work.

She was frail, and constantly sick.

She even bought a plot for her casket.

“I couldn’t be in a room and watch my kids playing,” Patricia said, wiping a tear away. “I would have to run in another room and cry, because I would just look at them as orphans.”

One of her toughest moments was telling her young son, Shawn, when he was 8 years old.

“He just withdrew. He sat around the house. He didn’t go out to play.”

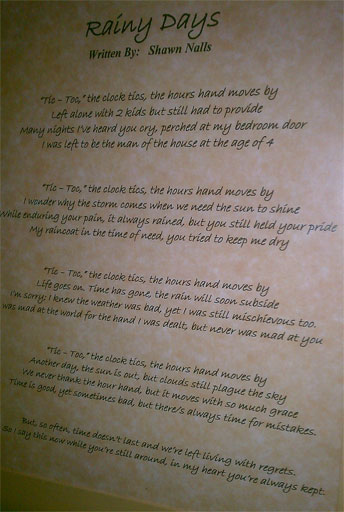

It was a poem Shawn wrote to his mom that eventually turned the tide, and the hard-headed kid she adored had returned.

Patricia started to regain her health when treatment drugs, such as azidothymidine (AZT), started to pop up in the late 1980s and early 1990s. In those days she was taking a regimen of up to 25 pills a day.

Now, she’s on a less intensive regimen of four treatment pills: Reataz; Viread; Sustiva; and Norvair.

“Four pills, once a day, at night, before I go to bed. It’s such a difference,” Patricia says.

Like many patients on similar regimens, she has suffered some side effects.

“I have diabetes. I have high cholesterol. I have bone issues,” she says.

She takes medications for those issues, and says she has her good days and her not-so-good days.

Living a normal life

“I just keep going. I’m like a little machine,” she says.

She gives credit for that to her staff, her clients, and her family.

“I would never, ever have thought that I would see my kids graduate from high school, graduate from college, my daughter’s engaged, and I have a grandson,” Patricia says.

The life of a survivor.

THE WOMEN’S COLLECTIVE

Patricia went through what she calls an “isolation” period when first dealing with how to live the rest of her life with AIDS.

To help her cope, she started to attend support groups. The problem was, in some cases, she was the only women to attend.

“The guys were great. They were wonderful, but they weren’t dealing with children,” Patricia said. “So when I started to talk about my panic attacks around ‘What will happen to my kids?’ they would kind of dismiss that, and kind of move onto what they were dealing with.”

She didn’t fit in. So in 1990 she took matters into her own hands.

She put up a flyer in her doctor’s office. She set up a private phone line in her home. She wanted to give women a place to call if they needed an ear to voice their fears, their anger, their laments.

Pat Nalls talks about how the Women’s Collective came to be.

“Low and behold, the phone started ringing. We just started talking on the phone, because none of us wanted to show our face,” Patricia said. “And eventually I started a support group in my home.”

It was called the Coffee House. Women went to eat, cry, and talk about what would happen to their children once they were gone.

“How do we prepare for death and protect our children, because back then there wasn’t any hope,” said Patricia of the conversations that took place.

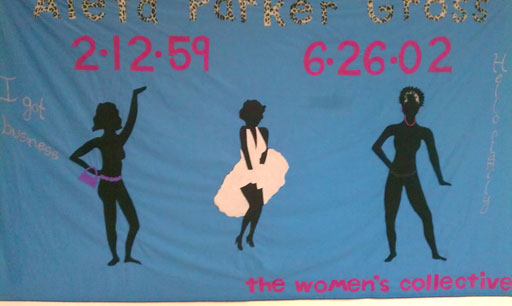

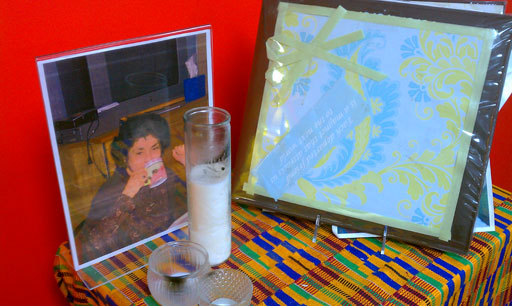

Some of the women did pass away, but the group kept going in their honor. As the number of women who came grew, so did the meeting spaces.

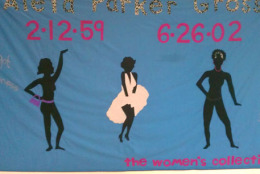

From Patricia’s home the group moved to the cafeteria in St. Anthony’s of Padua church in Northeast D.C. It was there that her organization became officially known as The Women’s Collective.

When the church space got too small, it was onto Dupont Circle, and then to an office in the U Street corridor.

In 2009, Patricia moved her organization to its current space in the Brentwood neighborhood in Northeast.

The agency handles, on average, about 300 cases of HIV-positive women. It also is the lone agency in the District that strictly serves women in the city living with HIV/AIDS.

Shawn, who did not want her last name used, has been a client for more than 15 years.

“If we didn’t have the Women’s Collective here a lot of women would’ve probably committed suicide,” Shawn said.

Shawn talks about what the Women’s Collective means to her.

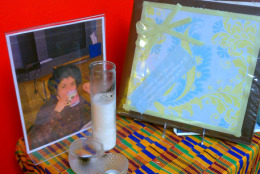

Shawn contracted AIDS from her husband, and was pregnant with her third child when she was diagnosed. Her son Daniel was born HIV-positive. He died from AIDS-related illnesses in 2007 at the age of 18.

“These groups of women helped me overcome, and maintain my sanity through support,” Shawn said.

The staff at the Collective is comprised of all women. Some are HIV-positive themselves.

“It’s more of a sisterhood that happens in here. So women don’t feel like they’re talking to a social worker, or a therapist. It’s more like talking to a sister,” Patricia said.

The women are assigned a case worker. Along with providing food and counseling, the agency offers free HIV tests to both men and women.

Patricia said getting women housing is the biggest issue she’s currently dealing with.

Most of the women who come to the Collective are minorities. When it comes to serving their needs, Patricia speaks very passionately.

It’s also why many of the women who make it through training programs at the agency become advocates.

“We want you to sit at tables where decisions are being made about our lives,” Patricia said. “And often times people like us are not at those tables.”

Carol, who also asked that her last name not be used, is one of her advocates, and also still a client. She says a conference the Collective sent her to last year was an eye opener.

“I learned so much,” Carol said. “And it really put me on fire to do stuff in the community that I live in, which is Ward 7 and Ward 8.”

Carol contracted AIDS in 1989 from a man with whom she had unprotected sex. She doesn’t blame the man who gave her the virus. Instead, she’s decided to use her situation as a learning tool for others.

“I’m on a mission. I’m gathering information and material because I’m going to take it to the street,” Carol said.

For Shawn, a 25-year-AIDS survivor, the agency has been a life line.

“Without the Women’s Collective, I would’ve drowned,” she said.

Related content:

- Listen to Meghan Davies of the Whitman Walker Health talk about HIV/AIDS in the District

- Whitman Walker

- Generation Positive – Part 1

Follow WTOP on Twitter.

(Copyright 2012 by WTOP. All Rights Reserved.)